Nearly vertical cliffs rising more than 6 kilometers (3.7 miles), extreme radiation levels, and temperatures dropping to −90°C (−130°F) are just some of the challenges future explorers would face when attempting to conquer Olympus Mons on Mars, the highest mountain and the largest volcano in the Solar System. Altezza Travel takes a closer look at what such an ascent would really involve.

The summit of Olympus Mons as a symbol of Mars exploration

Throughout history, humanity has been driven forward by a desire to explore the unknown. During the Age of Discovery, this dream gave people the strength to search for new lands. After the first sailors reached previously unknown islands and continents, thousands of travelers followed. Step by step, they explored plains and mountain peaks, until the maps of the world were finally free of blank spaces.

In the twentieth century, human ambition turned toward space. In 1969, a human foot first touched the surface of the Moon, and almost immediately, the idea of exploring Mars entered public discussion. In 2020, SpaceX founder Elon Musk announced his ambition to build 1,000 spacecraft and relocate around 1 million people to Mars by 2050. The first launch, initially planned for 2026 and unmanned, was later postponed to 2028, when Earth and Mars would align in the most favorable positions for such a mission.

A crewed test flight is unlikely to occur before 2033–2040, even under the most optimistic estimates. Yet sooner or later, humanity will face the question of how to mark the completion of the first stage of Martian colonization. Many believe the most powerful and symbolic act would be the ascent of Olympus Mons, the colossal mountain rising above Mars's surface.

What is Olympus Mons?

Systematic observations of Mars began as early as the nineteenth century, but for a long time, astronomers could see only a bright patch where Olympus Mons is located today. On the earliest maps of Mars, this region was labeled Nix Olympica (“Snows of Olympus”). Scientists believed it might be an ice deposit, as telescope technology at the time did not allow them to resolve finer details.

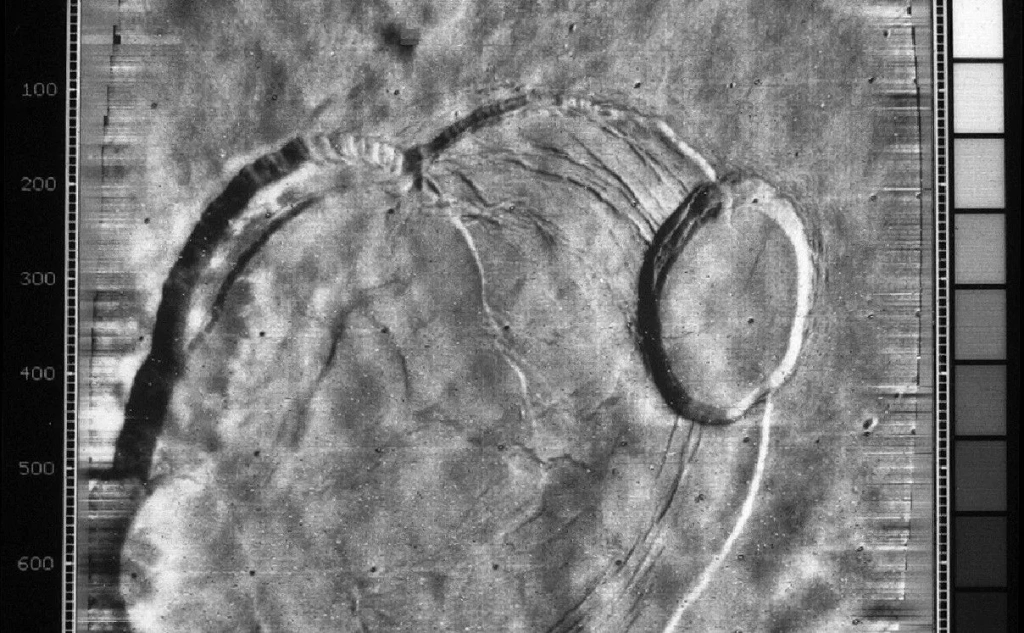

The answer came only in 1971, when the Mariner 9 interplanetary probe reached the Red Planet. Images transmitted back to Earth revealed that the mysterious bright spot was in fact the tallest mountain in the Solar System. To maintain continuity with earlier maps, scientists named it Olympus, using the Latin designation Olympus Mons.

A volcanic island in an ancient ocean

Further analysis of the images showed that Olympus Mons is an extinct volcano with an almost perfectly circular shape. The diameter of the ancient caldera is around 70 kilometers (43 miles), while the base of the mountain stretches up to 601 kilometers (374 miles) across. Surrounding the volcano is a network of smaller ridges and mountains known as the Olympus Aureole, which extends up to 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) from the summit. The total area of this mountain system is comparable to the combined size of France and Poland.

How Tall is Olympus Mons?

The height of Olympus Mons above the average Martian surface is about 21.2 kilometers (13.2 miles), and from base to summit it reaches roughly 26 kilometers (16.2 miles). This is several times higher than Mount Everest, Earth’s tallest peak at 8.8 kilometers (5.5 miles).

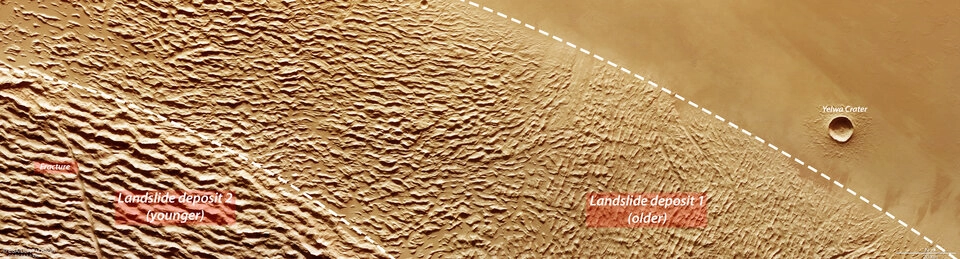

One of the most striking features of Olympus Mons is its steep, sometimes nearly vertical escarpments, rising 6 to 7 kilometers (3.7–4.3 miles) along the mountain’s edges. For decades, scientists debated how these dramatic cliffs formed. A breakthrough came in 2023, when the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter photographed a folded, heavily eroded region surrounding the volcano’s northern flank.

A research team led by Anthony Hildenbrand of Paris-Saclay University published a study in October 2023 suggesting that Olympus Mons resembles volcanic islands on Earth, such as the Azores, the Canary Islands, and Hawaii. The distinctive shape of its steep surrounding slopes may indicate that around 3.4 to 3.7 billion years ago, Olympus Mons was an island rising from an ancient Martian ocean roughly 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) deep. As lava flowed from the volcano’s vent and interacted with coastal waters, massive landslides formed, some of which extended for nearly 1,000 kilometers (620 miles).

A discovery made in 2024 suggested that this ancient ocean may not have vanished entirely. Scientists from the European Space Agency combined observational data from the Trace Gas Orbiter and Mars Express and found strong evidence of regular frost formation on the summit of Olympus Mons. The frost lasts only a few hours at night and evaporates after sunrise. Its thickness is just 0.01 millimeters, but the total amount of water deposited in this way reaches about 150,000 tons, enough to fill 60 Olympic-size swimming pools.

Conquering Olympus Mons

Who first proposed climbing Olympus Mons

One of the first people to publicly voice the idea of climbing Olympus Mons was the renowned Russian explorer Fyodor Konyukhov. Over the course of his life, he has completed several dozen expeditions, including multiple solo circumnavigations of the globe.

In 2002, for example, Konyukhov crossed the Atlantic Ocean alone in a rowing boat in just six weeks. In 2004–2005, he became the first sailor in history to complete a solo, nonstop circumnavigation on a maxi-class yacht via . Altogether, he has traveled approximately 257,500 kilometers (160,000 miles) solo across the world’s oceans. That distance is equivalent to nearly six and a half journeys around the Earth along the equator.

In 2012, Konyukhov climbed nine of Ethiopia’s highest peaks. In 2015, he summited Mount Everest via the North Ridge from the Tibetan side. In 2020, Fyodor Konyukhov and his sons climbed Africa’s highest mountain, Mount Kilimanjaro. The expedition was run by Altezza Travel.

In April 2024, Konyukhov said in an interview that he dreams of conquering Olympus Mons:

“My dream is to climb Olympus Mons on Mars. It is an extinct volcano and the tallest mountain in the Solar System. Its height exceeds 20 kilometers, with sheer vertical walls. I envy those who will land on Mars and be able to climb Olympus. If I had another three hundred years, I would dedicate them to preparing this expedition.”

The challenges of climbing Olympus Mons

Pressure, temperature, and radiation

Scientists already have enough data to model in detail how the ascent of Olympus Mons might be carried out by our near descendants. The first and most immediate challenge would be the extremely thin atmosphere. The average atmospheric pressure at Mars's surface is about 610 pascals, roughly 160 times lower than on Earth. At the summit of Olympus Mons, pressure would drop even further, to just 70–100 pascals.

Under such conditions, humans can survive only inside a fully pressurized spacesuit. Existing spacesuits are designed to operate in similar environments, although an expedition to the “summit of Mars” would require significant engineering improvements.

The second major challenge is temperature. During the Martian summer, daytime temperatures at the base of Olympus Mons can occasionally rise to a relatively comfortable +27°C (81°F). At night, however, temperatures can fall to −70°C (−94°F), and on the summit they can drop as low as −90°C (−130°F). In theory, this problem can also be addressed through advanced thermal protection in spacesuits.

A far more serious obstacle is radiation. Long-term measurements from the Mars Odyssey spacecraft show that radiation levels in Mars orbit are about 2.5 times higher than those aboard the International Space Station, reaching roughly 20 millirads per day. This is about 36 times higher than radiation levels on Earth’s surface. Prolonged exposure without adequate shielding could lead to severe health consequences, including increased cancer risk and damage to cells and DNA.

Cliffs and plains

When a Martian climber begins the ascent from the Olympus Aureole, the summit will not be visible. Due to the volcano’s enormous size, it lies far beyond the horizon. Instead, the climber would face a relatively steep lower slope bordered by sheer cliffs rising 6 to 7 kilometers (3.7–4.3 miles) along the mountain’s edges. Ascending such terrain would be extremely difficult even on Earth.

On Mars, the climb would be further complicated by low gravity, which is about 38 percent lower than Earth’s. On the one hand, walking and jumping would feel easier, as a person’s effective weight would be roughly 2.6 times lower. On the other hand, stopping after a jump or controlling momentum would be much more difficult.

Once the climber reaches the main slopes of Olympus Mons, the ascent becomes deceptively easier. The average incline here is only about 5 degrees. As a result, the final 300 kilometers (186 miles) would resemble a long, exhausting trek rather than a technical climb. At a good pace, this stage alone could take up to two weeks. The key challenges would be carrying enough food and oxygen and deciding where to rest, either inside spacesuits or within mobile shelters.

The tallest mountains in the Solar System

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do different sources list different heights for Olympus Mons?

Because “height” can mean either summit elevation above the planet’s reference level or the volcano’s total rise from its base.

Two methods are used. Absolute height is measured from sea level (or, on Mars, an average surface reference) to the summit. Relative height is measured from the mountain’s base to its peak, which can be much larger. Mauna Kea is a classic example: ~4,200 m (13,800 ft) above sea level, but ~10,203 m (33,475 ft) from seabed to summit.

Could Olympus Mons erupt again?

Possibly. Some researchers think Mars still has a rising mantle plume that could reactivate volcanism in Tharsis.

The youngest lava on Olympus Mons is estimated at about 2 million years old. A U.S.–Netherlands team analyzing NASA InSight data argued that a hot mantle plume is slowly rising beneath the Tharsis region. It may rise only 1–2 cm per year, but if it approaches the volcanic province, it could reheat magma systems and trigger eruptions, potentially affecting one volcano or several.

What would a climber see from the summit of Olympus Mons?

Mostly a flat, rocky desert. The summit is so broad and gently sloped that the view looks like a plain to the horizon.

Olympus Mons is enormous, and its upper slopes are shallow, so the “top” does not feel like a sharp peak. A climber would likely see a barren landscape stretching outward with little sense of dramatic height. Even the first summit photos could look underwhelming, because it would be hard to tell whether the person is on the Solar System’s highest mountain or on a flat plateau.

Is it possible to fall from the summit of Olympus Mons?

Not really. Near the top, the slope is so gentle that you would struggle even to slide downhill.

That said, the volcano’s outer margins are a different story. Olympus Mons is ringed in places by steep, nearly vertical escarpments several kilometers high, and those cliffs would be the real fall hazard.

Have Mars rovers explored Olympus Mons?

No. Rovers have not landed there because the altitude, thin air, and uncertain surface conditions make a safe landing and driving extremely difficult.

The mountain’s great height and Mars’s already thin atmosphere reduce the effectiveness of parachutes and complicate descent. Aircraft-style drones are also limited. On the ground, thick loose dust and unknown subsurface structure could trap or immobilize a rover. Most Olympus Mons research relies on orbital imagery and remote measurements from missions such as Mars Express and other spacecraft, plus broader geophysical data from missions like NASA InSight.

All content on Altezza Travel is created with expert insights and thorough research, in line with our Editorial Policy.

Want to know more about Tanzania adventures?

Get in touch with our team! We've explored all the top destinations across Tanzania. Our Kilimanjaro-based adventure consultants are ready to share tips and help you plan your unforgettable journey.