Numerous mountains across the globe test the limits of the most skilled and courageous mountaineers. Many of these peaks, such as Everest and K2 — the tallest in the world — and Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain, have already been conquered. However, despite advancements in technology and modern climbing equipment, there are still many virgin peaks today.

Before we dive into the list of the highest unclimbed peaks in the world, it's important to clarify a few things. A mountain remains unconquered if it lacks an official confirmation of anyone ever reaching its top. However, there are still gaps in the recorded history of mountain climbing. This is particularly true in remote regions of the world where existing records often lack verification. Even where records exist, some may lack evidence of authenticity. Of course, the emergence of GPS trackers and other modern equipment has made it much easier to document such achievements. Nevertheless, we still lack reliable data on certain mountains that may have been climbed in the distant past.

For instance, archaeological excavations in the Andes — the longest continental mountain range in the world, stretching along the western edge of South America — prove that humans climbed to altitudes of up to 6,739 m (22,110 ft) in prehistoric times. At the summit of the Llullaillaco volcano, researchers discovered preserved mummies and remnants of ancient structures, offering insights into prehistoric human activity. This was described in detail in Johan Reinhard and Constanza Ceruti’s book: "Inca Rituals and Sacred Mountains: A Study of the World's Highest Archaeological Sites".

In this article, we've gathered a list of six summits that mountaineering experts unanimously recognize as unclimbed peaks. They are not the tallest, but undeniably among the most challenging.

Gangkhar Puensum

Elevation: 7,570 m (24,836 ft)

Location: Northern Bhutan, on the border with Tibet

Gangkhar Puensum is the world's highest unclimbed mountain, with its main peak reaching 7,570 m (24,836 ft). It was first described in 1922, but topographical inaccuracies led to a long-standing debate about whether it belonged to China or Bhutan, as the mountain straddles their shared border. However, its main summit lies in Bhutan, whereas a significant portion of the massif extends into Tibet.

"Gangkhar Puensum" translates from Dzongkha, the official Bhutanese language, as "White Peak of the Three Spiritual Brothers". In addition to the main peak, the mountain has two secondary summits, 7,532 m (24,705 ft) and 7,516 m (24,650 ft) high. Local inhabitants consider the mountain sacred, and partly due to religious beliefs, climbing here was banned in 1994 when Bhutan prohibited ascents to mountains higher than 6,000 m (19,685 ft). In 2003, all mountaineering activities on Gangkhar Puensum were officially stopped.

While Everest reaches a higher altitude at 8,848 m (29,029 ft), Gangkhar Puensum’s 7,570 m (24,836 ft) presents formidable difficulties. Though the summit of Everest has already been reached numerous times by the boldest and most experienced climbers the legendary Bhutanese mountain remains an untouched challenge.

Throughout mountaineering history, four documented attempts have been made to reach this exceptionally challenging peak. In 1985, a team of eight climbers from the Himalayan Association of Japan, led by Michifumi Ohuchi and Yoshio Ogata, ventured to ascend the mountain via the southern ridge. After establishing their first camp at 5,220 m (17,126 ft), they found the route too dangerous. The alpinists then explored the western ridge but ultimately returned to their original plan, finding it equally unfeasible.

The Japanese team reached 6,490 m (21,296 ft), where they established their second camp. From there, they ascended to a jagged ridge, which they nicknamed "Dinosaur Ridge". They moved beyond two steep rocky steps and established their third camp at 6,880 m (22,572 ft). However, the team encountered a series of setbacks. One climber had to descend due to pulmonary edema, and another suffered injuries after falling from a . As a result, the team leaders decided to abandon the expedition.

Later that same year, an American team led by Philip Trimble also attempted to conquer Gangkhar Puensum. Their failure was partly attributed to the route they were allowed to take by the local government. The climbers were only permitted to approach the summit via the Chamkhar Glacier, but no feasible routes were found there. All requests by the American team to change their direction were denied.

In the following year, 1986, an Austrian group led by Sepp Mayerl made the third attempt to reach the summit. The team climbed to an altitude of 6,300 m (20,669 ft) but was forced to retreat due to strong monsoon winds. That same year, a fourth attempt was made by a British-American-New Zealand group led by Steven Berry arrived at a base camp at 5,180 m (16,994 ft) during a heavy rainstorm. After navigating the treacherous moraines of the Mangde Chu Glacier, the mountaineers established their base camp at 6,250 m (20,505 ft). Like the Japanese alpinists from the first mission, they managed to traverse "Dinosaur Ridge" but ultimately failed to reach the summit due to excessively strong winds.

As previously mentioned, in 1994, Bhutan prohibited climbing peaks over 6,000 m (19,685 ft). However, just four years later, in 1998, the Chinese Mountaineering Association issued a permit to a group from Japan to attempt the highest unclimbed mountain from the southern side. The Bhutanese government strongly opposed this unauthorized decision, which ultimately prevented the Japanese climbers from proceeding. Since then, Gangkhar Puensum has continued to hold the title of the tallest virgin peak in the world.

Lapche Kang II

Elevation: 7,250 m (23,786 ft)

Location: Tibet, China

The summit of Lapche Kang II, part of the Lapche Kang massif, is located in the Northern Himalayas. This section of the renowned mountain range remains poorly studied and, to this day, lacks detailed maps.

The highest peak of the massif is not Lapche Kang II, but Lapche Kang I. The main summit, standing at 7,367 m (24,154 ft), was first conquered by a Chinese-Japanese squad in 1987. Several climbers ascended it the same year, but for 23 years, no one dared to climb this part of the mountain again. In 2010, an attempt by American alpinist Joseph Puryear ended in tragedy — he fell to his death.

During the first ascent of Lapche Kang I, Japanese climbers noticed another nearby peak, approximately 7,072 m (23,207 ft), and named it Lapche Kang II. Later, in 1995, a Swiss team reached it. However, as it turned out, this peak was not the second highest. To the east of Lapche Kang I lies another summit, standing at 7,250 m (23,786 ft), officially identified as Lapche Kang II. Despite this, many sources still mistakenly refer to it as the third mountaintop.

The first and only attempt to climb Lapche Kang II occurred in 2016. A Polish team led by Krzysztof Mularski attempted to climb Lapche Kang II but was restricted by Tibetan authorities from using the northern route. Instead, the government suggested approaching from the east, which posed serious difficulties.

After reaching 6,600 m (21,654 ft), the climbers established their third camp before attempting the final ascent. However, this way was so challenging that the mountaineers were forced to abandon it. The new route led them up a 65° snow-and-ice wall to an altitude of 6,907 m (22,626 ft). Shortly after the start, they realized that continuing was too risky and dangerous. The group stopped their mission, leaving Lapche Kang II unconquered.

Apsarasas Kangri I

Elevation: 7,245 m (23,770 ft)

Location: China and India

The Apsarasas Kangri massif, including the Kangri I peak, is located in the Siachen Muztagh, a subrange of the Eastern Karakoram. China controls about 60% of this mountainous region, while India governs the remaining 40%. Territorial disputes in this area remain unresolved to this day. India claims parts controlled by China, while Pakistan contests areas governed by India. Because of these political issues, many mountaintops in the region have been closed to climbers for years.

As with Lapche Kang II, there has been some confusion regarding the numbering of peaks in this area. Early climbers mistakenly believed they had reached the highest point, naming it Apsarasas Kangri I. However, according to Eberhard Jurgalski, who holds the most comprehensive and accurate data on the world’s highest peaks, they actually climbed Apsarasas Kangri II. Be aware that many sources still incorrectly label these peaks.

In reality, Apsarasas Kangri consists of one primary peak and several subsidiary summits. The main and tallest is Apsarasas Kangri I (7,245 m / 23,770 ft), followed by the subpeak Kangri II (7,239 m / 23,750 ft).

Apsarasas Kangri II is the only peak in the massif that has been successfully climbed. This occurred in 1976 when a team from Osaka University in Japan reached the southern summit using the western ridge. Eight climbers were stranded there for a week due to heavy snow and strong winds. When the weather finally cleared, four of them succeeded in summiting Apsarasas Kangri II.

Meanwhile, Apsarasas Kangri I, the tallest peak spanning disputed territories between India and China, remains unconquered.

Tongshanjiabu

Elevation: 7,207 m (23,645 ft)

Location: Bhutan and China

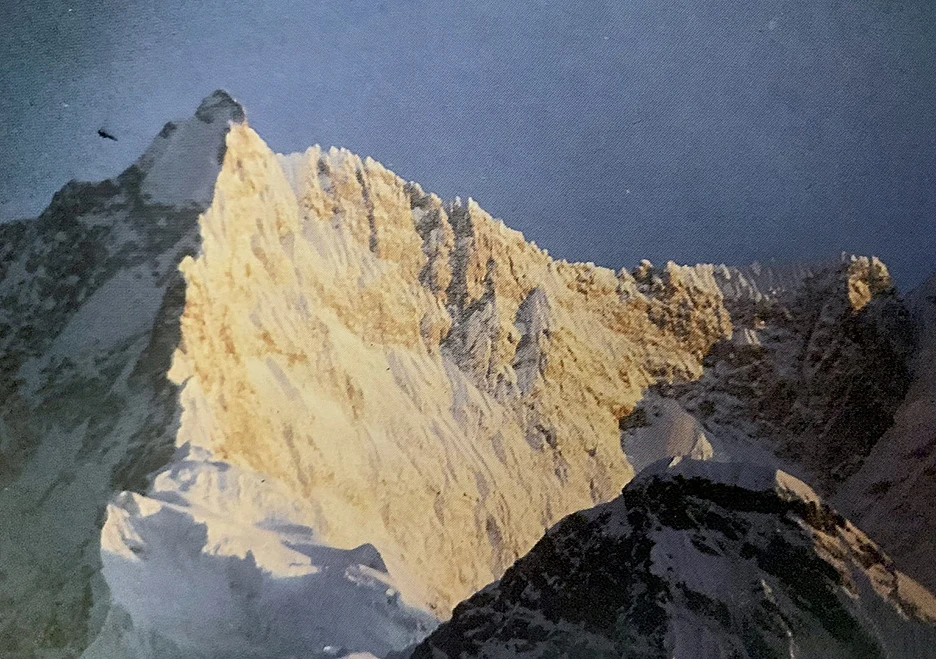

Tongshanjiabu has a challenging name and stands at 7,207 m (23,645 ft). It lies on the disputed border between Bhutan and Tibet. It is unclear if its climbing permits are currently available, as no recent attempts have been recorded. Even more intriguing, Tongshanjiabu is barely mentioned in the history of global mountaineering. No direct attempts to summit the mountain have been recorded, and even its high-quality photographs are exceedingly rare.

In 2000, a team from Japan, led by Kinichi Yamamori, explored mountain peaks in an obscure part of Tibet. Some of them were successfully climbed, while others remained unreachable due to washed-out roads and the danger of avalanches. Following this expedition, two members investigated nearby territories. Upon reaching an altitude of 5,275 m (17,306 ft), they captured the first-ever photographs of the faces of several unclimbed peaks, including Tongshanjiabu.

In 2002, a South Korean group became the first to ascend Kangphu Kang I, a nearby peak standing at 7,204 m (23,635 ft). Afterward, interest in climbing other peaks in the region waned due to the challenging conditions and lack of accessible paths. The Himalayan Association of Japan even filed a request for permission for Tongshanjiabu, but the outcome remains uncertain. It is unclear whether an attempt was made and failed or if the request was denied altogether, as official records do not clarify.

Praqpa Kangri

Elevation: 7,134–7,156 m (23,406–23,478 ft) according to different sources

Location: Pakistan

Taking fifth place among the tallest unconquered mountains in the world is Praqpa Kangri, also known as Praqpa Ri. This is another mountaintop from the Karakoram mountain range in Pakistan that has yet to feel the touch of a human climber.

It was only in 2016 that Canadian mountaineers Nancy Hansen and Germany’s Ralf Dujmovits attempted to climb Praqpa Kangri after receiving the Shipton-Tilman grant. Nancy, by then had completed 46 of the 50 classic climbs of North America. Ralf was the 16th person to summit all the mountain tops over 8,000 m (26,247 ft) (nearly all of them without supplemental oxygen). They spent two months trying to ascend Praqpa Kangri. Ultimately, upon reaching an altitude of 6,300 m (20,669 ft), they were forced to stop the attempt due to heavy snowfall.

Another documented event took place in 2021. Germans Martin Sieberer and Simon Messner could not reach the main summit due to steep slopes and deep snow. They reached only up to 6,000 m (19,685 ft). After returning from the expedition, Messner explained that the mountain slopes were excessively steep and prone to avalanches. He also emphasized that good weather was crucial for any safe attempt at the summit.

Mount Kailash

Elevation: 6,638 m (21,778 ft)

Location: Tibet, China

Mount Kailash is not the tallest among the virgin peaks, but it is undoubtedly one of the most famous and mysterious. Located in the western part of the Tibetan Plateau, it is considered sacred.

Pilgrims from various religions circumambulate Kailash as part of sacred rituals. According to Hindu legends, Kailash is made of pure silver, and Shiva — one of the supreme gods in Hinduism — resides at its top. Buddhists believe Kailash is the home of Buddha in one of his incarnations. Jains — a religious group originating in India — believe that their first saint achieved moksha, or liberation from the cycle of life and death, on this mountain. Bonpos — the adherents of Tibet's native Bon religion — worship Kailash because they believe the founder of their faith descended to this sacred place from heaven. For them, Kailash is a source of vital energy.

Despite Kailash’s significant appeal to mountaineers, it remains unclimbed, largely due to its sacred status. To this day, there is no official ascend record.

In the 1920s, the Brits Hugh Ruttledge and R.S. Wilson attempted Kailash. Ruttledge planned an ascent via the northeastern ridge but was unable to progress far due to weather conditions. Wilson explored the mountain from a different side along with a sherpa named Tseten, who assured him that the best route to the summit lay through the southeastern ridge. Wilson later wrote about how heavy snowfall halted his attempt, forcing him to abandon the climb.

Further mentions of Kailash appear in the works of Austrian writer and mountaineer Herbert Tichy. In 1936, while near the mountain, he too planned an ascent. When he asked locals about his plans, one religious leader responded:

“Only a man entirely free of sin could climb Kailash. And he wouldn't have to actually scale the sheer walls of ice to do it. He'd just turn himself into a bird and fly to the summit”.

Nyima Samkar, “Mount Kailash: The White Mirror Ngari, Tibet”

Later in the 1980s, renowned Italian alpinist Reinhold Messner received permission from the Chinese government to ascend Kailash. However, he ultimately stopped the mission, citing respect for local religious values.

The most recent attempt to climb the great Tibetan mountain happened in 2001. A Spanish team submitted a request for permission, which sparked significant outrage among religious devotees. The Chinese authorities were forced to deny the request, and they subsequently banned all future attempts reach the top of the mountain. To this day, Kailash remains one of the world’s most mysterious and protected peaks.

Karjiang I: one of the previously unclimbed peaks

Until recently, at 7,221 m (23,691 ft), Karjiang I was one of the tallest unconquered peaks. Located in Tibet, near the border with Bhutan, its main southern point had remained inaccessible for years. Attempts were made in 1986 and 2001, but both expeditions failed. Later, in 2010, American climbers Joseph Puryear and David Gottlieb were denied permission to climb Karjiang I. They redirected their efforts to Lapche Kang, where Joseph Puryear tragically lost his life.

Finally, on August 14, 2024, the previously insurmountable Karjiang I was conquered by Chinese climbers Liu Yang and Song Yuancheng. This achievement marked the end of a decades-long saga of attempts to reach one of the world’s most inaccessible peaks.

Why are there still unclimbed mountains?

The primary reason there are still virgin peaks on the planet isn’t their height alone but their geographical remoteness and inaccessibility. Mountaineering expeditions in the Himalayas are extremely expensive due to logistical challenges, including transportation to remote areas, specialized gear, hiring guides, and securing permits.

Additionally, some peaks are closed for climbing due to their religious significance. Territorial disputes often add further obstacles by preventing climbers from obtaining access. If these political obstacles can be resolved in the future, we may soon hear about new mountaineering feats. However, many of these summits are too challenging to reach.

All content on Altezza Travel is created with expert insights and thorough research, in line with our Editorial Policy.

Want to know more about Tanzania adventures?

Get in touch with our team! We've explored all the top destinations across Tanzania. Our Kilimanjaro-based adventure consultants are ready to share tips and help you plan your unforgettable journey.