There are several theories about the etymology and meaning of "Kilimanjaro". Many researchers believe that the name of the famous African mountain range originated from the Swahili language, others find connections to the Chagga tribe, and some argue for the connection with the Maasai dialect. Each of these theories offers different interpretations of the name “Kilimanjaro.”

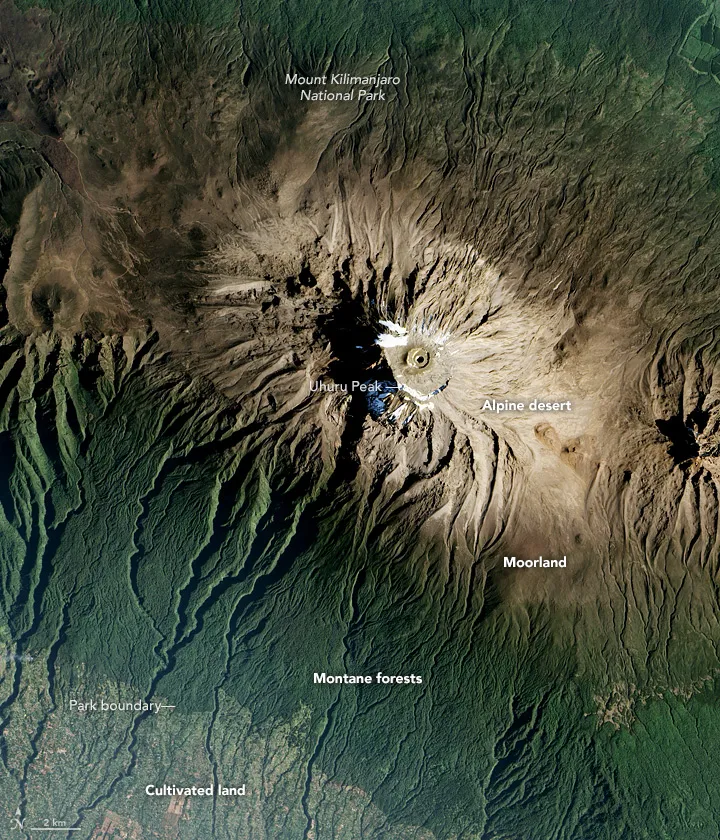

Located in northeastern Tanzania, near the Kenyan border, the snowy mountain Kilimanjaro is Africa's highest peak, with its central summit, Kibo, rising to 5,895 meters (19,340 feet). Interestingly, Kilimanjaro isn't just a single volcanic mountain but a dormant volcano range consisting of three peaks, each contributing to its striking alpine desert.

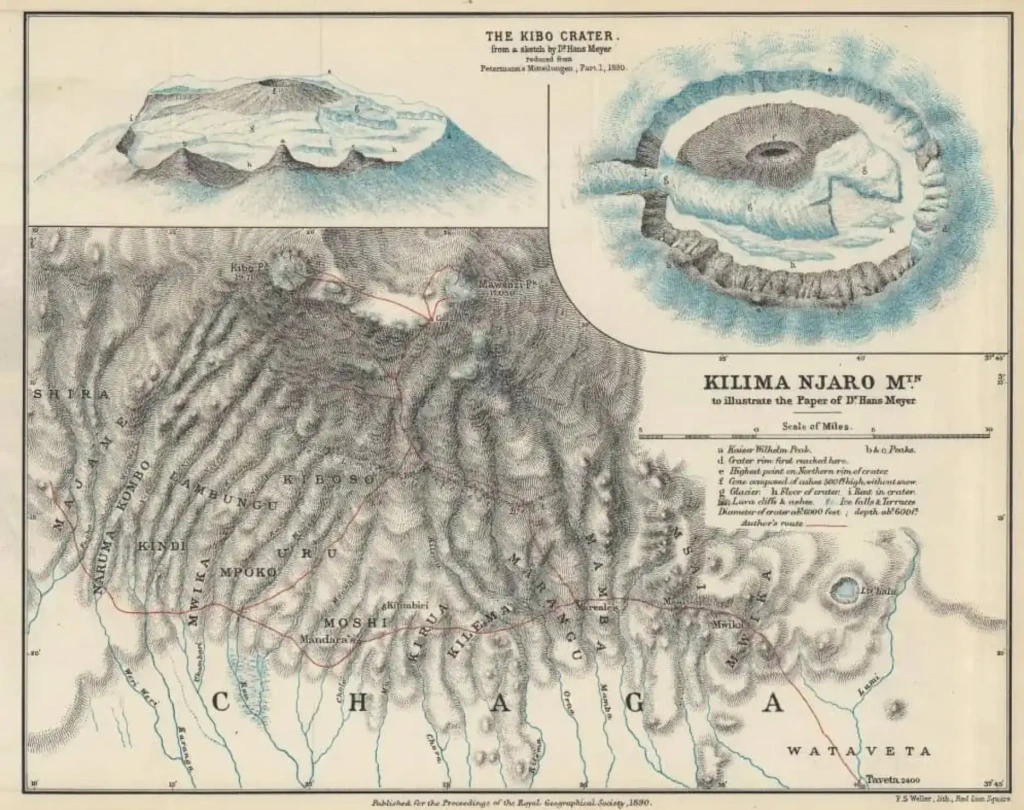

The first one to form here was Shira, which emerged around two million years ago and has since eroded almost completely. About a million years later, the Mawenzi volcano appeared next to Shira. After two eruptions, it also eroded, leaving only jagged outcrops as remnants of its former craters. The youngest of the three, Kibo, formed around half a million years ago. Its peak, known as Uhuru, is currently the only route open for tourists to climb Kilimanjaro.

The Roof of Africa is enveloped in a rich tapestry of legends and myths. One of its greatest mysteries is the origin of its name, Kilimanjaro, and what it actually means. Historians have yet to reach a consensus on this issue. To uncover the story behind this enigmatic name, let's first explore the earliest references to this snow-covered mountain range and then delve into the leading theories about the origins of its name.

How did the travelers reference to Mount Kilimanjaro?

Ancient times

The earliest descriptions of East Africa are found in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, dating back to 45 AD. This work is regarded as the world's first travel guide, serving as an ancient handbook for early explorers and sailors navigating the ports of Africa, Arabia, and India. The Periplus also provides detailed information about maritime routes to China.

In the pages of this ancient manuscript, the anonymous author describes a distant land called Azania and its thriving trading city of Rhapta. This remarkable place was renowned for selling rhinoceros horns, ivory, tortoiseshells, and other exotic goods.

Curiously, the Periplus makes no mention of the giant mountain with a snow-capped peak, which seems hard to miss. Researchers speculate that the author considered Rhapta to be the edge of the known world and thus saw no reason to explore beyond that area.

Less than a hundred years later, (circa 100–170 AD), an astronomer and the founder of scientific cartography, described lands lying south of Rhapta. According to him, they were inhabited by barbarian cannibals who lived near a wide, shallow bay. Within their country, one could find the “great snow mountain.” These lines are considered the first documented mention of Kilimanjaro.

It's worth noting that snow-covered mountains are quite rare and exotic in Africa. There are no other nearby peaks that could be mistaken for the continent's highest one. So, modern historians are confident that Claudius Ptolemy was indeed referring to Mount Kilimanjaro.

Middle Ages

However, no one mentioned the snow-capped mountain again until the sixth century, when Arab and Chinese traders arrived on the East African coast. At this time, references to a mountain “white in color” began to resurface. For instance, hints of Kilimanjaro can be found in the writings of Abu’l-Fida, a 13th-century Arab historian and geographer.

Renaissance

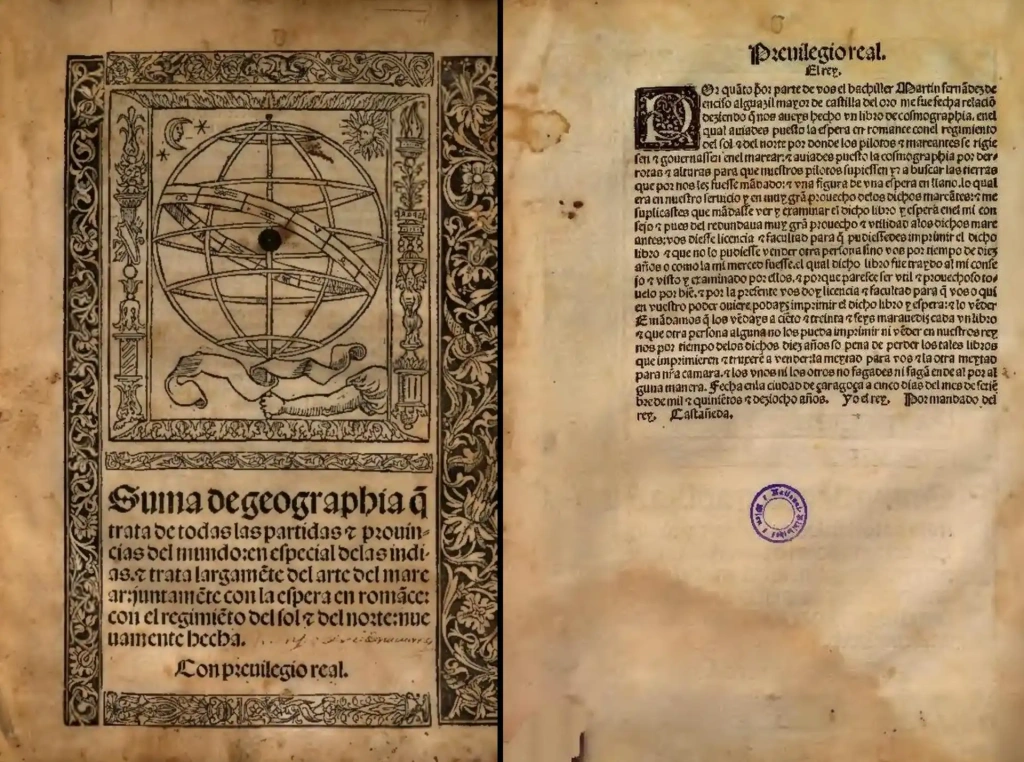

Many years later, a potential reference to Mount Kilimanjaro appears in the 1519 book Suma de Geographia, written by Spanish astronomer and navigator Martin Fernández de Enciso. In this work, the author describes his journey to Mombasa:

“West of Mombasa stands the Ethiopian Mount Olympus, which is exceedingly high, and beyond it are the Mountains of the Moon, in which are the sources of the Nile.”

Some researchers suggest that the “Mount Olympus” mentioned in the book might actually be Kilimanjaro. In this context, the “Mountains of the Moon” are believed to refer to the Rwenzori Mountains, which lie on the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. For many years, the Rwenzori Mountains were thought to be the source of the Nile.

Victorian Era

The name closest to the modern “Kilimanjaro” first appeared in the 1845 essay The Geography of N'yassi, or the Great Lake of Southern Africa Investigated, published in The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. In this work, the renowned geographer William Desborough Cooley introduced a name that closely resembles the one we use today:

“The most famous mountain of Eastern Africa is Kirimanjara, which we suppose, from a number of circumstances to be the highest ridge crossed on the road to Monomoezi.”

In his essay, Cooley either accidentally or deliberately misspelled the mountain's name. The exact reason for this distortion remains unclear to this day.

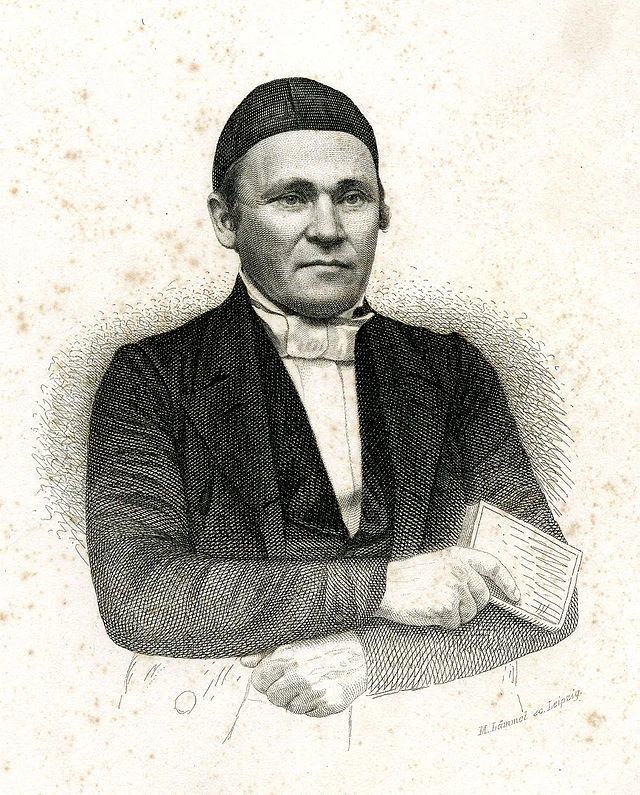

A year later, in 1846, Johannes Rebmann, a young Swiss-German missionary, arrived in Mombasa. His sole mission in Africa was to convert as many people as possible to Christianity, as Islam was already spreading actively in the region. In October 1847, Bwana Kheri, a local guide and caravan trader, offered to take Rebmann to a place he called “Dschagga”. According to Kheri, from there, one could see “the high mountain Kilimansharo.”

On April 27, 1848, Rebmann set out with Bwana Kheri and a caravan towards the mountain. That year, the missionary began keeping a journal, which he maintained until his death. In this journal, entries dated May 11 describe:

“This morning we saw the mountains of Dschagga (he refers to Kilimanjaro by the name of the area where it is located) clearer and clearer, until at about 10 I saw on the top of one of them a noticeable white clowd. My guide confirmed me and called it “baridi”, meaning “cold”; but I got obvious and sure that it can't be anything else than snow.”

Rebmann's description of the snow-capped mountain just south of the equator was published in The Church Missionary Intelligencer in April 1849. At that time, however, many people dismissed his findings. Prominent geographers, including Cooley—who had first called the mountain Kirimanjara—couldn’t believe that snow could exist in equatorial Africa. Cooley, for instance, found Rebmann’s account to be “incomprehensible, vague, and misty.” This skepticism about the possibility of snow in the region was widespread.

Remarkably, centuries before this debate arose, Claudius Ptolemy had already referred to the mountain as snowy, making an unexpectedly accurate prediction. It remains a mystery why scholars later dismissed this idea so rigorously.

For the next 12 years, Rebmann tried to convince geographers that snow did cover the summit of Kilimanjaro. Then, in the latter half of the 19th century, a new chapter in the mountain's history began as explorers set out to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, braving challenges like freezing temperatures, steep inclines, and the constant risk of altitude sickness. This era marked the beginning of the initial theories about the meaning of "Kilimanjaro."

Does "Kilimanjaro" have Swahili origins?

One of the most popular theories traces the name to the Swahili language. In 1860, Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German linguist, traveler, and fellow missionary of Rebmann, who played a key role in East African exploration, tried to unravel the “Kilimanjaro” meaning.

Mountain of Glory

In one of his seminal works, Travels, Researches and Missionary Labours During an Eighteen Years' Residence in Eastern Africa (1860), Krapf claimed that the term “Kilimanjaro” means “mountain of glory.” Apparently, the researcher believed that the Swahili word “kilima” translates to “mountain,” while “njaro” denotes “glory.”

Shining Mountain

In 1965, researcher J.A. Hutchinson published The Meaning of Kilimanjaro (Hutchinson, J.A., Department of Language and Linguistics, University College, Dar es Salaam), where he thoroughly examined the major theories regarding the origin of the mountain's name. He pointed out the lack of evidence supporting Krapf’s theory and suggested that Kilimanjaro's name could mean "Shining Mountain."

For instance, Hutchinson cites the words of Joseph Thomson, author of Through Masai land: a journey of exploration among the snowclad volcanic mountains and strange tribes of eastern equatorial Africa (1885). On page 207, Thomson writes:

“The term Kilima-Njaro has generally been understood to mean the Mountain (Kilima) of Greatness (Njaro). This probably is as good a derivation as any other, though not improbably it may really mean the “White” mountain, as I believe that the Swahili word “Njaro” has in formal times been used to denote whiteness, and though this application of the word in now obsolete on the coast, it is still heard among some of the interior tribes.”

Hutchinson explains that neither Thomson nor Krapf provided sufficient compelling evidence to support any of the theories. Yet it’s possible that the mountain’s name originated as an interpretation of the second part of the word: an old Swahili word “njaro” which means “shining", making mountain Kilimanjaro translate to "the Shining mountain".

Furthermore, Krapf, who referred to Mount Kilimanjaro as the “mountain of glory,” recounted his encounter with a chief of the people. He described visiting the chief in 1849: “had been in Jagga, and had seen the Kima ja Jeu, Mount of Whiteness, the name given by the Wakamba to the Kilimanjaro.” However, if translated accurately into Kikamba, this name would be “kiima kyeu.”

Critics point out that all these theories fall apart when considering that the Swahili word "kilima" actually means "hill," not "mountain." It's a diminutive form of "mlima," which is the correct term for "mountain." It’s hard to believe that local tribes would refer to the continent’s highest peak as just a hill. Many historians, therefore, think that the early Western explorers may have been confused by the local dialects and terminology.

In the 1880s, when the Kilimanjaro region became part of German East Africa, the Germans named the mountain Kilima-Ndscharo, drawing from the Swahili word. On October 6, 1889, , a German explorer and geographer, became the first European to climb Kilimanjaro and reach the highest point of the Kibo crater, which he named Kaiser-Wilhelm-Spitze (Kaiser Wilhelm Peak). After establishing Tanzania in 1964, the Kibo's crater rim was renamed "Uhuru Peak," meaning "Peak of Freedom" in Swahili. This name has proudly remained ever since.

Did Chagga people name the mountain Kilimanjaro?

Impossible for a bird/leopard

Another theory about the origin of "Kilimanjaro" suggests interpreting the name through the language of the local rather than Swahili. According to this theory, "kileme" might mean "that which defeats," while "kilelema" could translate to "difficult" or "impossible." The suffix "-jaro" could come from the Chagga word "njaare," meaning "bird," or, according to other sources, "leopard." If this is the case, the mountain's full name might translate to "Impossible for a bird/leopard."

Mountain of caravans

In addition to his “Mountain of Glory” theory, Krapf also suggested that “Kilimanjaro” might be a hybrid name, blending elements from both Swahili and Kichaga, the language of the Chagga people. In this interpretation, “Kilimanjaro” could be translated as “Mountain of caravans,” with “jaro” possibly meaning “caravans” as well.

Critics point out that this theory has its flaws, mainly because the Chagga tribe sees Mount Kilimanjaro as two separate peaks rather than a single mountain, naming each one individually—Kibo and Mawenzi. “Kibo” comes from the Chagga word kipoo, meaning “spotted,” likely referring to the dark rocks against the white snow. “Mawenzi” is derived from kimawenze, meaning “broken” or “notched,” which describes the rugged, jagged nature of its summit.

Given that the Chagga people didn’t use the word “Kilimanjaro,” some researchers suggest another possibility: the name might not be a single word but rather a phrase suggesting that climbing Kilimanjaro is impossible because it is too challenging and impregnable.

Is the name Kilimanjaro derived from the Maasai language?

The language is another potential source for the name “Kilimanjaro,” and there are a few different theories. For example, the Maasai word “ngare” means “source of water.”

Mountain of water

In his 1893 book Mission to Kilimanjaro, Archbishop recounts the following story after discussing other theories:

“At Taveta, we were taking a walk with some local children. One of them asked us if we had to stay a long time at Kilimanjaro. I replied, “What are you saying? Kilima-Njaro? But what does that mean, Njaro?” — “It is ‘water’. And that big mountain over there is called 'the mountain of water' because all the rivers here and everywhere come from there.”

White Mountain/Mountain of Whiteness

This explanation seems plausible, but it also has its drawbacks. For example, the Maasai word “njaro” can also mean “whiteness,” which relates to the snow-covered mountain's peak. Therefore, a more accurate translation could be “White mountain/Mountain of Whiteness” rather than “Mountain of water.”

Mountain of Spirits

A third hypothesis is linked to the belief in evil spirits. For example, local lore speaks of a demon named Njaro that resides at the summit of Kilimanjaro. Hutchinson found references to this legend in the works of explorer A. G. Fischer, specifically in his “Report of a Journey in the Maasai Country,” published in the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, Vol. VI, 1884. On pages 70-83, Fischer writes:

“The Maasai word (Kilimanjaro) does not mean either ‘mountain’ or ‘greatness’, but signifies Njaro Mountain, by which among the inhabitants of the coast, an evil spirit is meant.”

, a British African explorer, in his 1886 work The Kilima-Njaro Expedition, also explains the name of Kilimanjaro mountain as deriving from the word kilima — meaning “mountain” — and njaro, which refers to a demon believed to cause deadly colds. Sir Johnston asserts that this name is known only to the coastal inhabitants and is unfamiliar to those living in the interior regions.

Several other notable figures in the history of Kilimanjaro have also referenced the mystical origins of its name. For instance, the German geographer Hans Meyer, the first known European to reach Kilimanjaro's summit, supported this notion. In his 1891 book Across East African Glaciers, he writes on page 152:

“We awoke, in capital trim for our climb to the summit, and this time Njaro, the spirit of the mountain, was propitious. At last—we succeeded in reaching our goal.”

Meyer also mentions the spirit on page 154:

“Njaro, the guardian spirit of the mountain, seemed to take his conquest with a good grace, for neither snow nor tempest marred our triumphant invasion of his sanctuary.”

Based on Meyer’s descriptions, it’s likely he was referring to the legends of the Chagga tribe, who believed in a guardian phantom at the summit of the Kilimanjaro mountain, unlike the Maasai who spoke of an evil spirit.

Critics point out that the issue lies in the absence of a Maasai word equivalent to "kilima." This has led to a new theory suggesting the name “Kilimanjaro” might be a hybrid of both Swahili and Maasai elements. According to this theory, the name could be translated as “Mountain of water,” “White mountain,” or “Mountain of the Evil Spirits.”

To this day, historians and researchers have not agreed on the meaning of “Kilimanjaro”. Many theories exist, and the true explanation might be somewhere between them all. For now, we must choose the theory that we find most convincing.

All content on Altezza Travel is created with expert insights and thorough research, in line with our Editorial Policy.

Want to know more about Tanzania adventures?

Get in touch with our team! We've explored all the top destinations across Tanzania. Our Kilimanjaro-based adventure consultants are ready to share tips and help you plan your unforgettable journey.