Every year, visitors flock to Tanzania to relax on the stunning beaches of Zanzibar and enjoy the warm waters of the Indian Ocean. However, many don’t realize this paradise once had a dark and painful past.

For centuries, Zanzibar was the site of one of the largest slave markets, where countless Africans were forcibly traded by Arab merchants. The atrocities of the slave trade continued into the 20th century, with some reports suggesting that it persisted as late as the 1960s.

This article explores Zanzibar’s troubling past, highlighting the profound impact of the slave trade on its history.

The roots of slavery in East Africa

There are no precise records of when slavery first began in Zanzibar. Researchers believe it started in the 8th century, long before the Arabs began migrating to East Africa's coast. Even earlier, local ethnic groups were fighting among themselves, capturing and enslaving their enemies and selling them.

When the Arabs arrived in Zanzibar, they quickly took control of the slave trade and expanded it to an immense scale. Thanks to Zanzibar’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean, it became a key hub for selling enslaved people to Oman and the wider Middle East. With ruthless efficiency, the Arab rulers turned the trade into a major industry. Within a few centuries, it made up a third of the Sultanate’s income, alongside profits from ivory and cloves.

“Zanzibar was an ivory and slave trading centre before the Omanis came to settle. But during the period of Sayyid Said’s reign Zanzibar more than doubled the value of its exports and brought most of the coastal towns under its financial control. By the 1860s slave exports approached 30,000 a year and an efficient machine, backed by Indian capital, had been created to funnel slaves into the island from all over East Africa. Cloves, introduced by Mauritius and Reunion in the 1820s, gradually became Zanzibar’s third export after ivory and slaves, and the plantations absorbed so much labour that by the 1850s an estimated two thirds of the population of the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba were slaves”. Asian and African Systems of Slavery, Edited by James L. Watson, 1980.

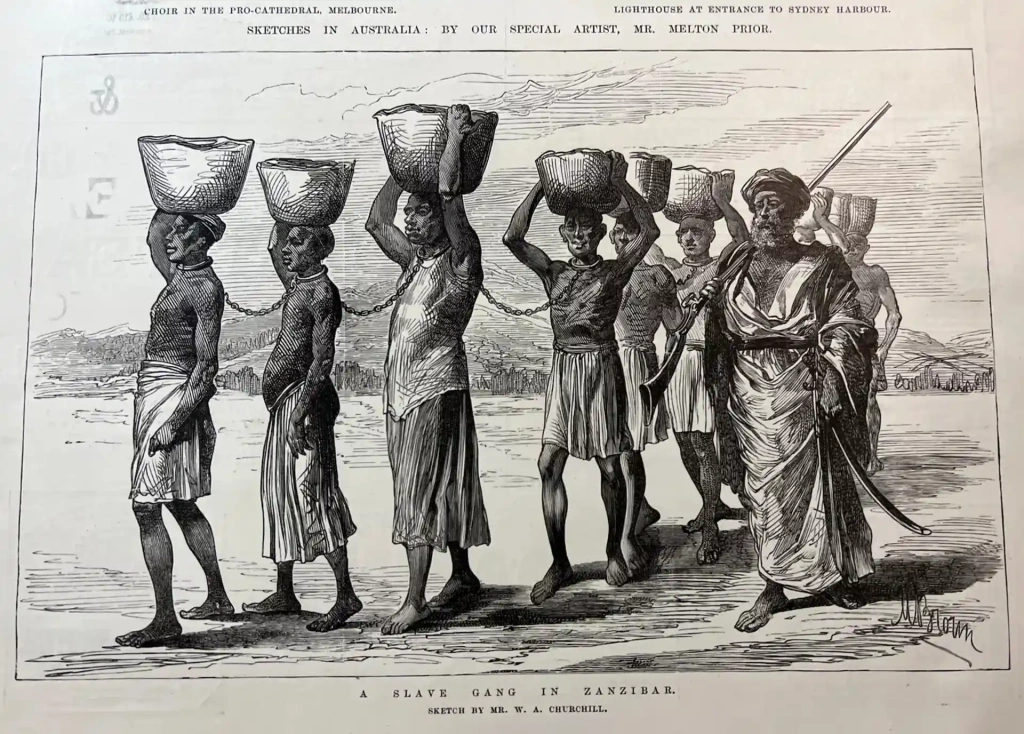

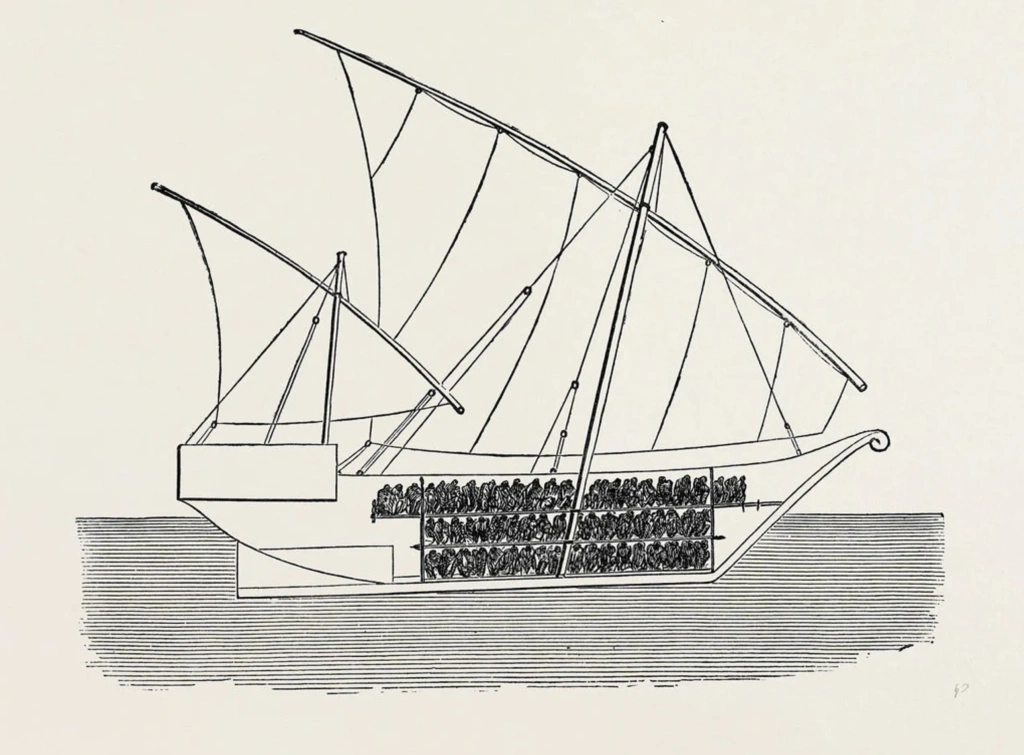

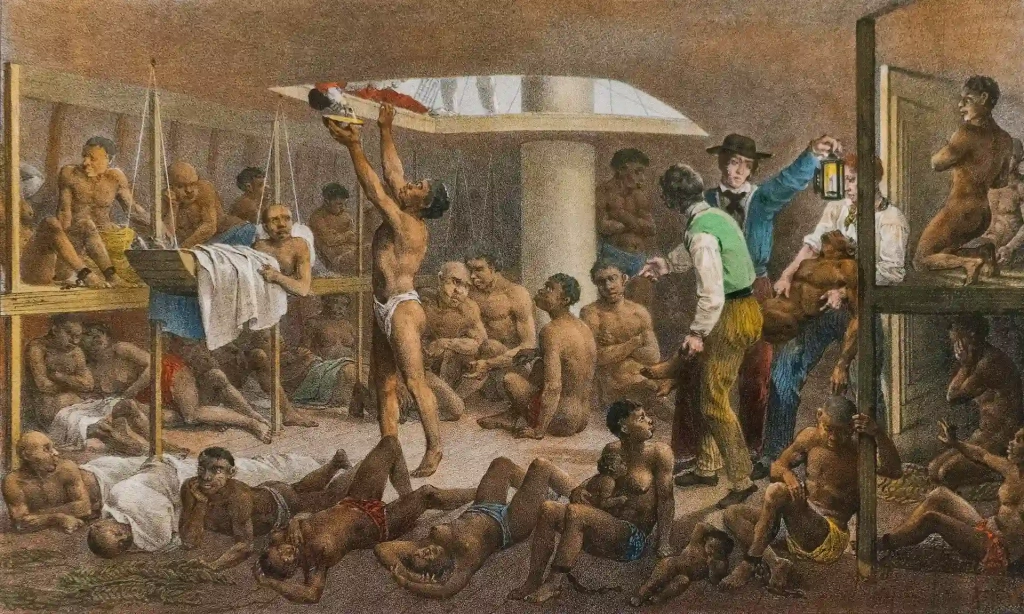

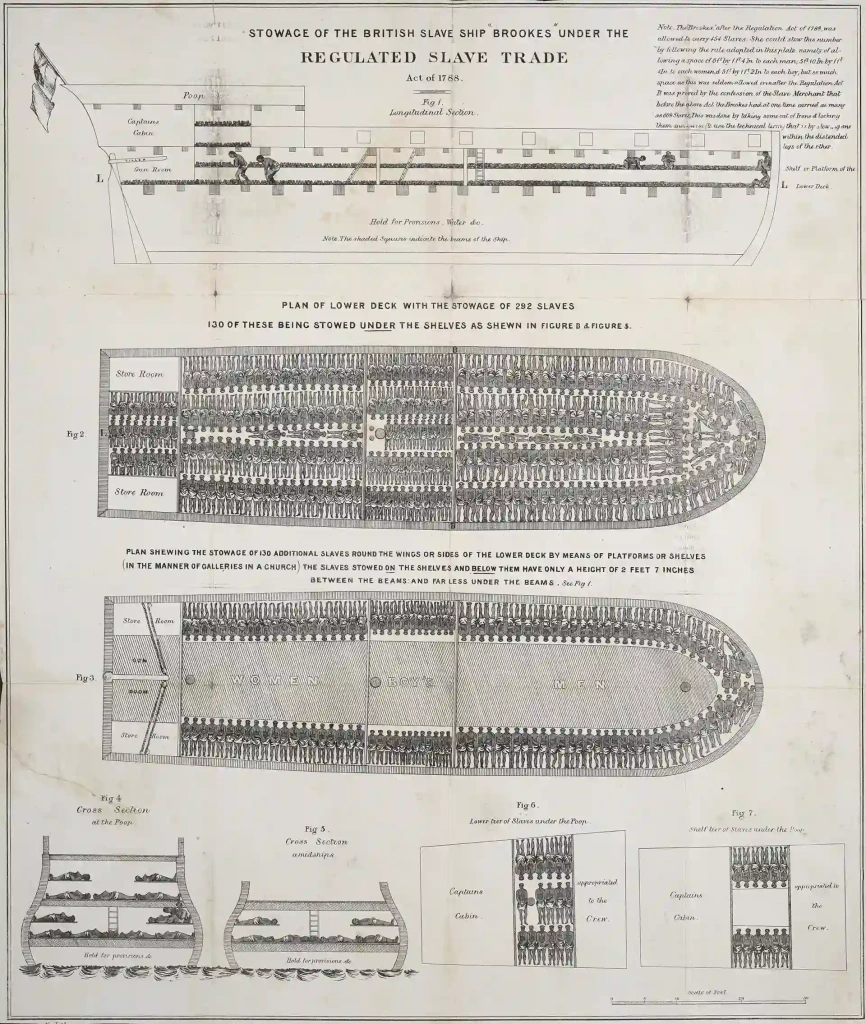

Slaves were transported on large ships specifically designed for carrying "live cargo." To maximize profits, shipowners crammed as many people on board as possible. The captives were shackled in heavy chains and confined to extremely tight spaces with limited oxygen in the holds. As a result, many slaves died during the journey and were thrown overboard.

During the Portuguese influence in 1684, European lawmakers introduced the Tonnage Act, slightly improving transportation conditions. However, this was likely not driven by humanitarian concerns but rather by a desire to increase profits. After all, if too many of them arrived dead at the slave market, no one would pay for them.

Still, the conditions on these ships remained bad. People spent months in stifling heat, chained at their ankles and necks, sitting naked on the floor, beaten and hungry, driven mad by grief and terror. On each journey, many simply could not endure and died from dysentery, malaria, smallpox, and numerous other diseases.

As British influence gradually grew, the Dolben Act was passed in 1788. This decree limited the number of slaves transported based on the ship's cargo capacity. Although this decree was applied only to British ships, it marked the first official government initiative in the United Kingdom to regulate the slave trade. , a prominent advocate for the abolition of slavery, introduced the act in Parliament.

Sir Dolben joined the abolitionist movement after visiting a slave ship, “Brookes,” in the port of London by accident. The horrific conditions in which people were kept in chains shocked him so deeply that he immediately launched a campaign to fight this inhumane practice.

William Dolben documented the ship, which later became world-renowned. In 1788, engravings of “Brookes” were published and became a symbol of the inhumane treatment of African captives. This widespread publicity was a powerful catalyst for passing the aforementioned bill, which restricted “Brookes” to carrying no more than 454 people. Before this, it had transported over 600 slaves at a time.

Slaves on Zanzibar

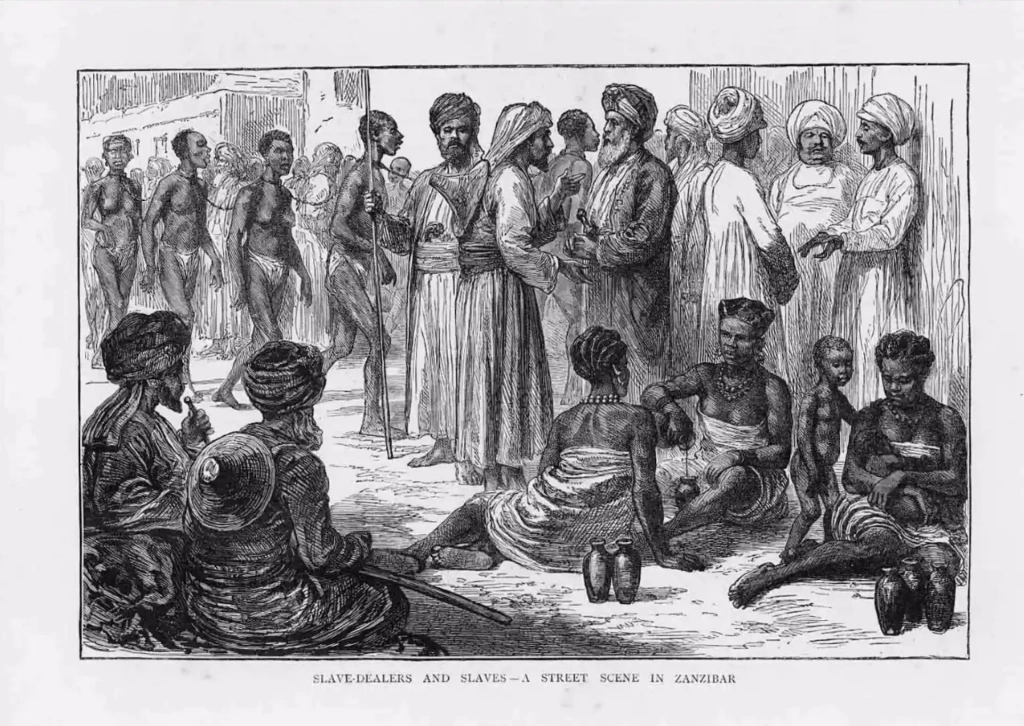

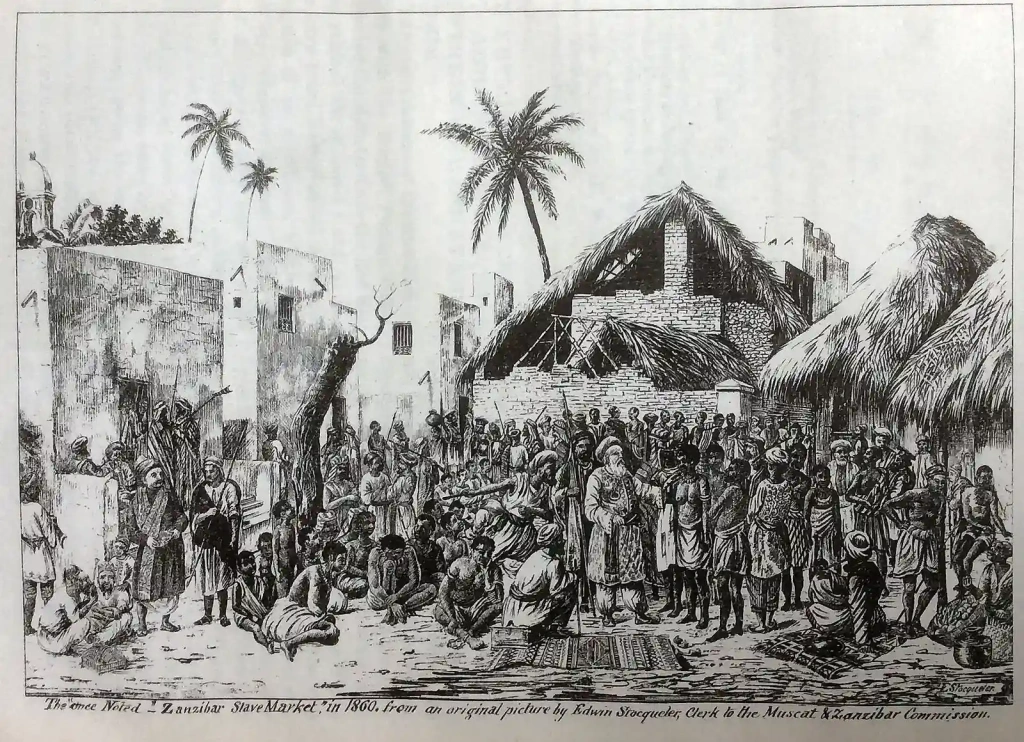

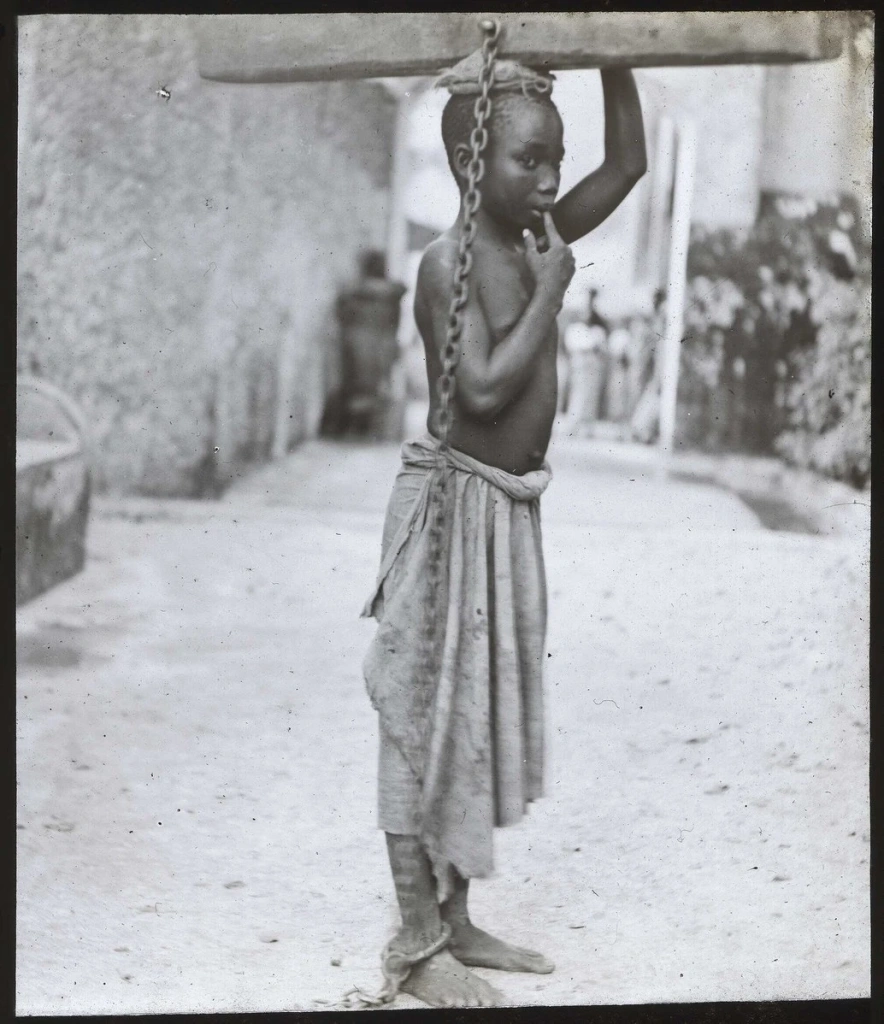

In the 19th century, the island of Zanzibar became one of the main global centers for buying and selling people. By the 1850s, up to 70,000 slaves were on the island. Captives from Central Africa were transported to the East African coast in numerous caravans and on fishing dhows. From there, the weakened and half-dead slaves were brought to Stone Town. They were literally “dumped” into cramped underground cells, where they had to wait until the slave market opened, usually around four in the afternoon.

Slave owners arranged their human “property” in rows, grouping people by age, gender, suitability for different types of work, and estimated value. Buyers would carefully inspect the “living goods,” stripping them naked to examine their eyes and teeth, feeling their muscles and other parts of the body. They made them move around to check for strength and physical defects. Some reports even mention how slaves were thrown sticks and told to fetch them, as if they were animals.

Women were given special priority. Arab countries purchased them to work as domestic servants or as sex slaves. In wealthy Muslim families, men would gather entire harems of concubines. Once enslaved, these women endured cruel treatment not only from their owners but also from the wives. A vivid example of this is presented in the book “Sex, Power, and Slavery,” edited by Gwyn Campbell and Elizabeth Elbourne, published by Ohio University Press in 2014.

In the book “Aspects of Colonial Tanzania History,” published in 2013 by Lawrence E. Y. Mbogoni, it is noted that children were also in high demand in the Zanzibar slave trade. According to the author, they were easier to manage, much like flocks of sheep. Girls, in particular, were more expensive. For instance, in 1857, a 7-8-year-old boy was valued at an average of 7 to 15 dollars, roughly equivalent to 255 to 545 dollars today. Meanwhile, a girl of the same age could cost between 10 to 18 dollars, or 360 to 655 dollars, when adjusted for current exchange rates.

After 1828, the demand for male slaves sharply increased. The Sultan implemented a strict plan for cultivating cloves, which led to a surge in the need for slave labor on the plantations. Experts estimate that by the 1850s, around two-thirds of the population of Zanzibar and Pemba Island were slaves.

Tippu Tip, the most famous slave dealer of Zanzibar

Countless people were bought and sold during the height of the slave trade. Many slave dealers amassed vast fortunes from the thousands of ruined lives. One of the most prominent figures among them was Tippu Tip, a slave trader of Afro-Omani origin.

Under his leadership, thousands of expeditions were sent to Central Africa, where they would purchase villagers for a pittance and forcibly take thousands of Black captives. According to one legend, the nickname “Tippu Tip” was given to him because of the distinctive sound of gunshots that invariably accompanied his raids.

Tippu Tip not only supplied slaves to Eastern trading ships but also traded large quantities of ivory. With his profits, he bought land and set up clove plantations, forcing hundreds of captives to work there. In Stone Town, an old stone house still stands, once owned by Tippu Tip.

Surprisingly, this man left his mark on history not only as one of the most successful and ruthless slave traders but also as an educated man. He was considered an intellectual and wrote the world’s first autobiographical treatise in Swahili. What’s particularly striking, however, is his support for David Livingstone, the renowned philanthropist and abolitionist.

Although Livingstone publicly condemned the slave trade, there was a time when he could not continue his research in Africa without the support of local benefactors. Unfortunately, many of these benefactors were slave owners. They, in turn, understood how to profit from this seemingly contradictory “friendship.” Livingstone had earned the trust and respect of the local people, which worked to the advantage of the wealthy Arab families who supported the Scottish missionary.

The fight against slavery and the beginning of its end

The abolition of the slave trade on the East African coast was not an immediate event. It was a slow, gradual process that met with strong resistance from the local Arab elite.

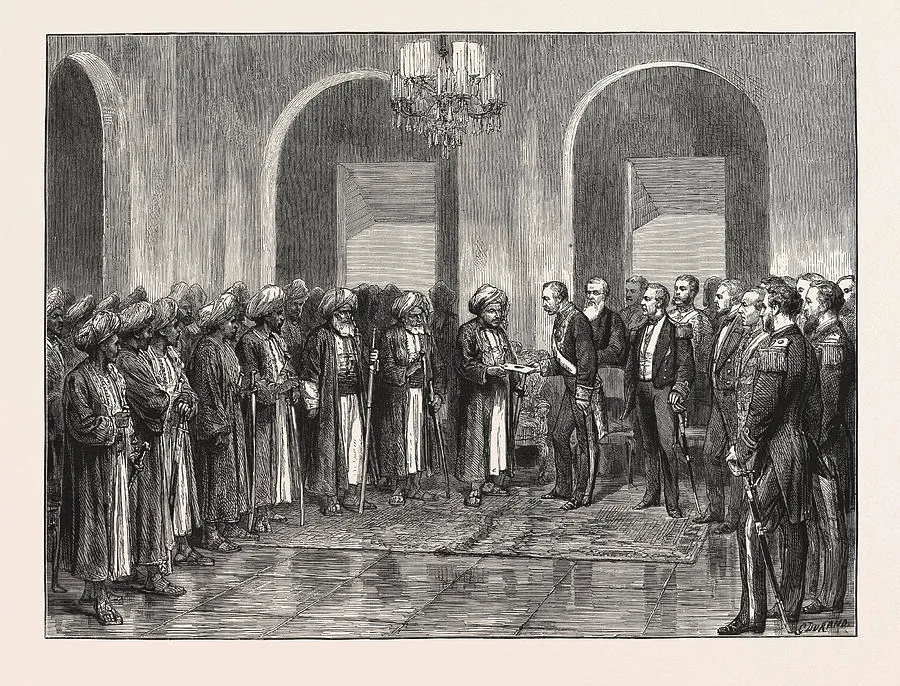

In 1822, the British signed an agreement with the Sultan to end human trafficking in the south and east regions. In 1845, the so-called Hamerton Treaty was signed, which limited the sale of slaves in the northern regions. In 1872, British colonial administrator Henry Bartle Frere traveled to Zanzibar to negotiate the complete cessation of the slave trade. By the following year, he succeeded in securing a treaty that required Zanzibar to stop importing slaves from the mainland to the islands.

However, that was not the end. Despite slaves being officially granted the right to seek help from the British if they were being sold against their will, the trade continued, though at a reduced pace.

In the same year, 1873, the open slave market in Stone Town was finally closed. However, this did not stop the local Arab authorities from shifting the trade to the neighboring, more isolated island of Pemba. The Sultanate continued to import thousands of slaves, and even the British fleet patrolling the coastal waters couldn’t stop this traffic.

«The trade in smuggled slaves was of particular importance in the history of Pemba. With the closing of the slave market in Zanzibar Town in 1873, Pemba became a major destination for imported slaves. It has been estimated that Pemba received as many as 1,000 slaves per month in 1875. The British navy regularly patrolled the waters around Pemba, and later skirmishes between naval vessels and slave-carrying dhows often occurred in Pemban waters. Because of this shift, Pemba became internationally known through Western newspapers as a place of slavery and resistance to the British treaties.» Slavery and Emancipation in Islamic East Africa: From Honor to Respectability, Elisabeth McMahon, 2013.

This situation continued until 1890, when, under pressure from the British, the Sultan finally issued a decree completely prohibiting the purchase, sale, and exchange of slaves. However, slavery itself was not entirely abolished. Slaves were given the opportunity to buy their freedom, and any children born after 1890 were automatically free by birth.

In 1897, the British forced the Sultan to abolish slavery in Zanzibar by declaring that it lacked legal status. However, this date cannot be considered the final point as the decree did not include concubines, as the issue was too sensitive in Arab culture for British interference. The Arab elite convinced British officials that, once freed, women who had been sexually enslaved would only be able to live as prostitutes. As a result, Europeans classified concubines as wives but left them in complete subjugation to their masters. The only concession was that they could apply for freedom, but only if there was evidence of cruelty or violence from their owner.

The final end of slavery, at least in the official context, came in 1909. The British finally forced the sultan to include concubines in the decree abolishing the slave system. However, even after this, human trafficking between Zanzibar and the Arabian Peninsula continued. Up until the end of World War I, Arab slave owners in Eastern Africa considered their servants as slaves and sold them on black markets.

According to unofficial sources, the illegal slave trade may have continued until the 1960s, when Zanzibar experienced one of its bloodiest revolutions. The Sultan was overthrown, and thousands of Arabs fled to the Arabian Peninsula and Europe. On April 26, 1964, Zanzibar united with Tanganyika to form a new nation, the United Republic of Tanzania.

The slavery museum in Stone Town – fragments of memory from a tragic past

Today, the Slavery Museum in Stone Town serves as a monument to those brutal times. The exhibition features the former slave market site along with documented evidence from the past, including official papers, photographs, and engravings depicting the horrors of the slave trade. However, perhaps the most chilling part of the museum is the underground chambers, where captives, shackled in heavy chains, awaited the opening of the market.

There are more than 20 such rooms beneath the museum, but the tour only includes access to two. However, that is enough to immerse oneself in the terrifying atmosphere and gain a deeper understanding of Zanzibar's history.

At the entrance to the former slave market site stands a memorial that sends chills down your spine at first glance. The doomed faces of the stone sculptures depicting African slaves are frozen in unbearable pain and despair. What is particularly striking is the chain binding the statues together. It is said to be original, preserved from those horrific times when the Zanzibar slave trade was an ordinary and familiar reality.

Near the old market stands the Anglican Cathedral, a monumental testament to the end of slavery in Zanzibar. According to some accounts, David Livingstone's heart is buried on its grounds, while his body was sent to the United Kingdom after his death.

Slavery in Zanzibar is undoubtedly a tragic part of history. However, it also serves as a reminder not only of the cruelty humans are capable of but also of the incredible resilience of the human spirit in the fight for freedom. Today, Zanzibar symbolizes both past suffering and renewal, where history and beauty coexist.

All content on Altezza Travel is created with expert insights and thorough research, in line with our Editorial Policy.

Want to know more about Tanzania adventures?

Get in touch with our team! We've explored all the top destinations across Tanzania. Our Kilimanjaro-based adventure consultants are ready to share tips and help you plan your unforgettable journey.