People climb Kilimanjaro for many reasons. Some are driven by scientific curiosity, studying its glaciers and unique wildlife. The challenge of exploring less-traveled paths draws others, while many simply seek the personal accomplishment of standing at Africa’s highest point.

The Altezza Travel team’s article highlights stories of both famous and lesser-known climbers whose journeys have become part of Kilimanjaro’s rich history.

The scientist ahead of the mountaineers

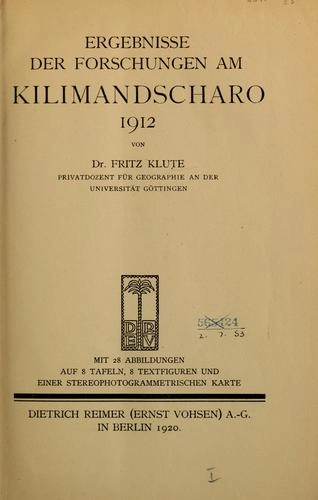

Fritz Klute holds a unique place in Kilimanjaro glaciology. Unlike most mountaineers, his goal wasn’t simply to reach the summit but to conduct a detailed study of the mountain’s glaciers. He was one of the pioneers of glaciology in Africa. While leading one of the continent’s first scientific expeditions, he also became the first person to climb Mount Mawenzi, part of the Kilimanjaro massif.

Klute studied natural sciences at the University of Freiburg in Germany. Just before his trip to Africa, in November 1911, he defended his doctoral dissertation on snowmelt in the Black Forest. His fascination with glacier dynamics likely fueled his interest in Kilimanjaro. It’s also possible that his companion and expedition partner, Eduard Oehler, who had visited Kilimanjaro in 1907 with his professor cousin, may have inspired Klute’s connection to the Roof of Africa.

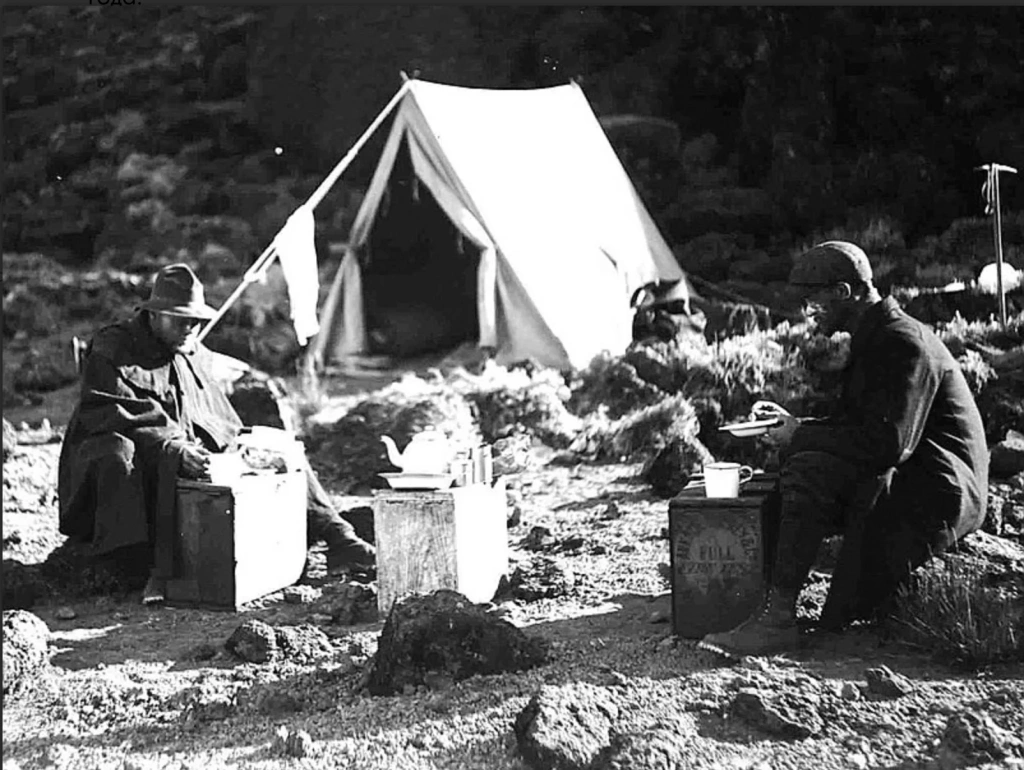

“On April 8, 1912, Eduard Oehler from Offenbach am Main and I left Freiburg on an early morning train to begin an expedition we had been planning for two months,” Fritz Klute recalled at the start of the journey.

According to Klute, Oehler also financed the expedition. Little else is known about him, although we can assume the German from Offenbach was a skilled athlete, as Klute describes him as an excellent skier.

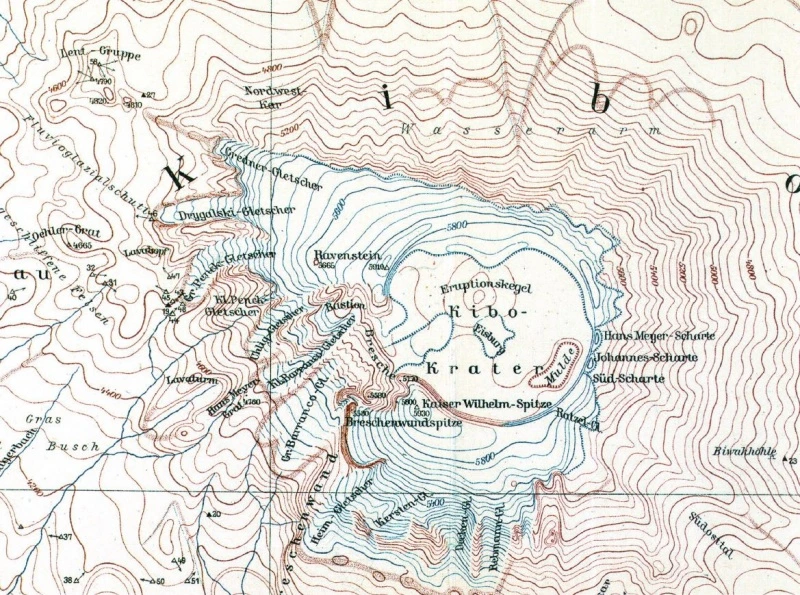

The main goal of the expedition was to map Kilimanjaro’s glacial fields, documenting their size and volume. Klute employed photogrammetry, a method combining photography with field measurements. In the summer of 1912, the expedition team carried out excursions and observations in the highlands, resulting in one of the earliest systematic studies of the mountain’s glaciers.

Their findings provided scientists with concrete evidence of the dramatic shrinkage of Kilimanjaro’s ice. In fact, Klute was the first to raise the alarm that the mountain’s ice cap could be at risk. After returning, he published his final scientific monograph, “Ergebnisse der Forschungen am Kilimandscharo,” in 1912.

However, Klute and Oehler chose not to limit their expedition to scientific work alone. Their attention turned to the unconquered peak of Mawenzi (5,149 meters / 16,893 ft), one of the three volcanoes of the Kilimanjaro massif, alongside Kibo and Shira. Only seasoned climbers could hope to scale this rugged summit.

Mawenzi had previously been attempted by Hans Meyer and Ludwig Purtscheller, who in 1889 completed the first successful ascent of Kilimanjaro’s highest point, Uhuru Peak (5,895 meters / 19,341 ft). Their three separate attempts on Mawenzi had failed, and subsequent climbers met the same fate.

Klute and Oehler launched their ascent on July 29, 1912, navigating a couloir that begins at the saddle between Kibo and Mawenzi. The steep slopes, rocks, and ice made the route extremely dangerous. Despite the challenges, they reached the summit, surveyed the Shira Plateau, and even visited Kibo’s crater.

For many years, it was believed that Klute’s field notes had been lost during the bombing of Gießen on December 6, 1944. The house on Moltkestraße, where the scientist lived, was heavily damaged. However, in 2024, German media reported a sensational find.

In August 2024, Mário Jorge Alves, a researcher at the Oberhessisches Museum, was assigned to locate ethnographic items stored in the building’s basement. While sorting through a pile of boxes and crates, Alves discovered Klute’s materials: eight photo albums and handwritten diaries from 1912.

Although these documents have not yet been digitized, it’s expected that they will soon reveal new details about the expedition of the glaciologist who dared to ascend the previously unconquerable rocky peak.

Conquering the Decken Glacier

One of the glaciers Fritz Klute mapped was the Decken Glacier, named after the German African explorer Karl Klaus von der Decken. While its coordinates, size, and surface conditions had already been recorded, no one managed to traverse this snow-and-ice cap until 1938. The first to do so were Klute’s fellow Germans Fritz Eisenmann and Karl Schnackig.

Since the late 19th century, Mount Kilimanjaro has lost more than 80% of its glacial surface. Scientists have noted that from 1912 to 1953, the ice cover shrank by approximately 1% per year, whereas from 1989 to 2007, the rate accelerated to 2.5% per year. Some models predict that all of Kilimanjaro’s glaciers could disappear entirely by 2040–2050.

Until recently, these glaciers posed nearly insurmountable obstacles for climbers. The Decken Glacier, a narrow ice couloir with a steep slope leading to the summit, is also exposed to the danger of falling rocks and ice. In short, it was the kind of challenge that would tempt any mountaineer, yet it remained unconquered until the mid-20th century. Records indicate that British explorers attempted to ascend it in the mid-1920s but were unable to navigate the ice crevasses.

The expedition to the Decken Glacier, funded by the German Alpine Club, was evidently led by Fritz Eisenmann. He had previously participated in several Himalayan expeditions and specialized in navigating challenging ice routes. He was accompanied by Karl Schnackig, a Swiss mountain guide experienced in Alpine climbs.

On January 12, 1938, according to reports, Eisenmann and Schnackig set out along the “original route,” starting at an elevation of around 4,650 meters (15,255 feet). Unfortunately, no archival records of the expedition have survived, but it is known that the two Europeans successfully completed the climb.

The Heim Glacier expedition

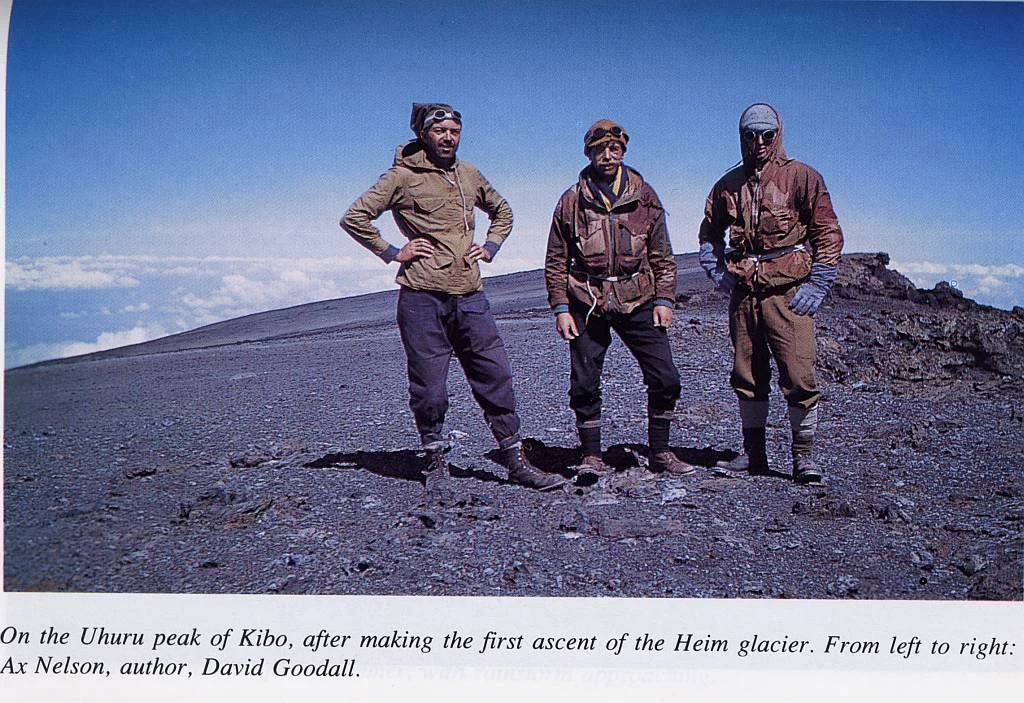

Twenty years after the events described above, British explorer John Cooke, author of the book “One White Man in Black Africa: From Kilimanjaro to the Kalahari, 1951–91,” nearly lost his life while attempting another Kilimanjaro glacier, Heim. At one point, he dangled over a precipice, saved only by a rope secured by his companion.

Named after the Swiss geologist Albert Heim, the glacier sits at an elevation of 5,000–5,800 meters (16,404–19,029 ft) in the Western Breach area. Heim has been likened to an ice “tongue” due to its icy projection over a steep slope.

“My plans for Kilimanjaro had been maturing for some time,” Cooke wrote. “All parts of the whole massif had been reached by mountaineers, geologists and surveyors, and the main summit of Kibo had been reached by thousands of people by the normal trade route of ascent from Marangu, which poses no technical problems. However, I could find no record of a complete, continuous traverse of the whole mountain, taking in all the main peaks of Shira, Kibo and Mawenzi. This I planned to do. A second aim was to attempt a first ascent of one of the unclimbed glaciers on the south face of Kibo”.

As the title of his book suggests, the British explorer spent forty years on the African continent. He worked in the colonial administration of Tanganyika and sought companions whenever he planned a risky route.

One of them was Anton Nelson, an American builder who had taken up rock climbing at age 27. In the early 1950s, he traveled to Africa to “assist the struggling farmers of the Wameru tribe in Tanzania”, and in his free time, he also climbed Kilimanjaro. At that time, the Wameru were protesting the transfer of part of their lands to European settlers by the Tanganyika government. Nelson became an advisor to a cooperative of coffee planters on Mount Meru and later wrote “The Freemen of Meru.”

The third member of the expedition, the British David Goodall, had served in a parachute regiment before taking a position as an agricultural officer in Kenya.

The team planned to spend two weeks on the mountain. By the time the expedition set out, their equipment was ready, but the route remained uncharted. Nelson persuaded an acquaintance, a tourist plane pilot, to fly over the glacier and take a close-up photograph of Heim, which the climbers used as a guide.

Their first goal was the Shira Plateau. From there, reaching the base of the glacier required a long traverse over scree and rocky terrain.

“About 3,000 feet (1,000 m) of steep ice reared upwards and curved out of sight far above us. It looked forbidding. The whizz and hum of flying ice and rock debris from above quickly drove us against the ice front below a protecting rock-wall, where we bivouacked. I felt butterflies in my stomach as one always does before a challenging venture,” Cooke described.

Thanks to the photograph taken by the pilot, the climbers knew that Heim’s main obstacles were two cliff lines in the lower third of the slope. It was at this point that the expedition nearly came to a disastrous end. Cooke, positioned in the middle of the rope team, slipped and dangled upside down over a precipice, suspended by the safety rope held by Goodall. With remarkable speed and precision, Goodall secured the rope before the full weight could fall on Nelson, who was last in line and barely holding onto the rock face himself.

The incident ended with the loss of only an ice axe, though it significantly slowed the expedition’s progress. In the thick fog, the lead climber had to drive in a piton, secure the safety rope, and then lower the ice axe on a rope to the climber following behind.

“We were on a vast slope which curved out of sight below us whence we had come,” Cooke recalled, describing his emotions at the end of the route. “In the clear air we had a breathtaking view directly out over the immense plains of northern Tanganyika. These huge isolated East African volcanic peaks stand proudly alone, and from their upper slopes there are no rivals to encumber and clutter the free surrounding space. We felt that we were literally on the roof of the world, and as success seemed within our grasp we felt a tremendous sense of elation.”

Scaling to the summit in 12 hours

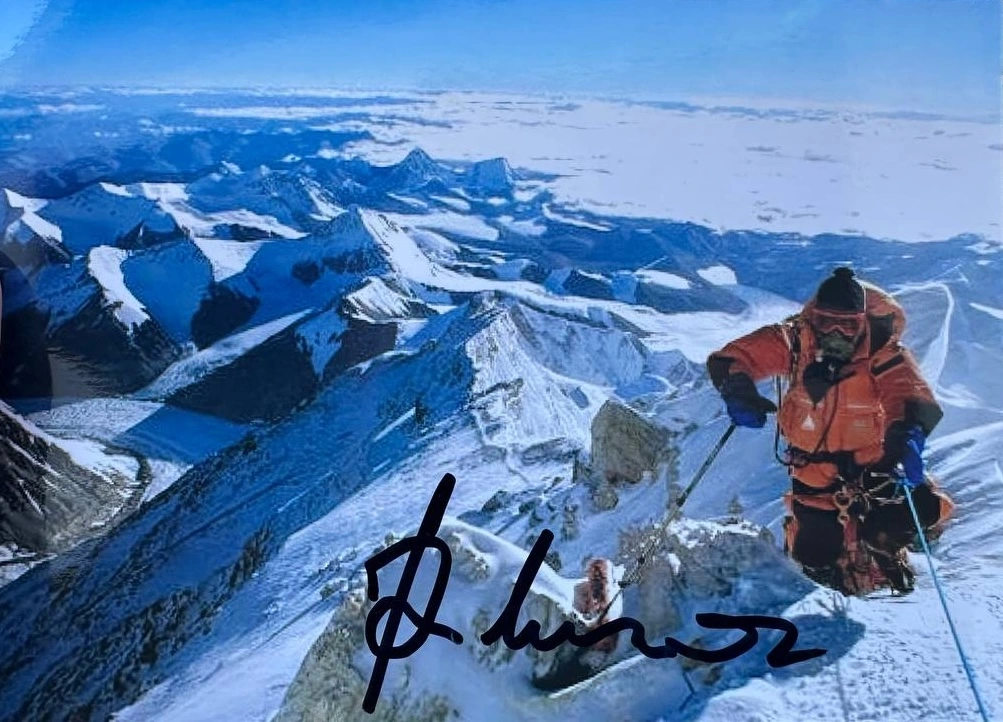

“Now Kilimanjaro can be considered a real mountain,” is a phrase reportedly spoken by the legendary Italian climber Reinhold Messner after completing the first successful ascent via the Breach Wall and Diamond Glacier in 1978. This steep rock-and-ice face on Kilimanjaro’s western slope leads through icefalls and a snow corridor directly to the summit.

Messner, holder of the honorary Golden Ice Axe award, is one of the world’s most famous climbers. Known for his extraordinary endurance, he pioneered fast solo ascents of the highest peaks without supplemental oxygen and was the first to conquer all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter mountains.

While preparing to climb Kilimanjaro via one of the classic routes with fellow climber Konrad Renzler, Messner planned to attempt an untraveled path to Africa’s highest peak. For an athlete of his caliber, the standard route was easy, but along the way, he became intrigued by the seemingly impassable western face.

The direct, shorter route to the summit via the Breach Wall begins at Arrow Glacier Camp and follows the volcanic rift straight to the top. It is the steepest and most technically challenging route on Kilimanjaro, bypassing gentler slopes to climb the vertical wall formed by the crater’s collapse. The path traverses icy and rocky sections, demanding exceptional skill and preparation.

Until 1978, this route was considered impassable. Reinhold Messner and Konrad Renzler completed the ascent in just 12 hours.

According to Summitpost.org, from the base of the Breach Wall (4,600 meters / 15,092 ft), the climbers first ascended via an icefall to the Balletto Glacier. They then tackled the 90-meter (295 ft) icicle of the Breach Wall at 5,450 meters (17,881 ft). After overcoming these obstacles, they traversed the Diamond Glacier north toward Uhuru Peak. Reports note that, in addition to its technical challenges, the route is particularly dangerous for teams due to rockfalls.

The Kilimanjaro guide who met them after the descent recalled Messner’s words: “Now Kilimanjaro can be considered a real mountain.” However, there is no documentary evidence to confirm that he actually said this.

More than that, mountaineering reviews in the Alpine Journal and on Summitpost note that Messner later described this ascent as “one of the dangerous ones.” In an interview with the German magazine Der Bergsteiger in October 1978, he recalled that “the ice was like glass, so the ice screws barely gripped.” In the sun, the ice turned into a liquid mush, making it crucial to choose the right time to tackle the route. Messner also noted that rocks breaking free from the ice fell like projectiles.

“Kilimanjaro showed me that the Alpine style is possible even in Africa. The Breach Wall is not a place for porters and tents, but for climbers confronting the mountain face directly,” he wrote in his book “The Big Walls,” summarizing the adventure.

“No place he would rather be than in the mountains”

Some cultures have traditions associated with dying on a mountain. In Japan, for example, there is the practice of , which translates to “abandoning the old woman.” For many mountaineers, climbing is life itself — yet some never make it back from the mountains. One such case was Ian McKeever, an Irishman who lost his life on Mount Kilimanjaro, not from exhaustion or altitude sickness, but from a sudden lightning strike.

Ian McKeever died on the slopes of Kilimanjaro at the age of 42, having only taken up serious climbing in his thirties. His career was both rapid and remarkable.

A graduate of the Faculty of Social Sciences at University College Dublin, McKeever also worked as a radio host and PR specialist before gaining international recognition as a climber. In 2004, he set a record for the Five Peaks Challenge, scaling the highest mountains in the United Kingdom and Ireland in just 16 hours and 16 minutes. Three years later, he broke the world record for completing the Seven Summits program, conquering the highest peaks on each continent in only 155 days.

McKeever also inspired a younger generation. In 2008, he guided his 10-year-old godson, Sean McSharry, to the summit, making him the youngest European to climb Kilimanjaro. That same year, under McKeever’s leadership, 145 schoolchildren reached the top of Kilimanjaro. That achievement was recognized by Guinness World Records and dedicated to raising funds for hospitals and charitable organizations.

Friends remembered Ian McKeever as an unstoppable dreamer who poured much of his boundless energy into charitable work. In 2010, he founded the Kilimanjaro Achievers organization, which offered free tours to schoolchildren with a passion for the mountains, sometimes as many as ten climbs a year.

In early January 2013, McKeever was once again leading one of the Kilimanjaro charitable climbs, guiding a group of 20 people to the summit. Among them were students, a teacher from an Irish school, and his fiancée, 34-year-old Anna O’Loughlin. The two were set to marry in September of that year. The team had reached an altitude of about 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) when the weather suddenly took a turn for the worse.

“Torrential rain all day,” McKeever wrote. “Spirits remain good even if drying clothes is proving impossible. We pray for dryer weather tomorrow – the big day.”

The group planned to reach the Lava Tower camp before continuing toward the summit. But the storm grew stronger, and by the time they neared the camp, a fierce thunderstorm had broken out. A lightning strike hit McKeever, claiming his life. The rest of the team, including his fiancée, who was injured in the storm, was evacuated to a nearby hospital.

One of the first to express condolences was the then Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny, who was well acquainted with McKeever.

“I admired him not only for his own achievements and charity work but also for his work with young people in challenging them to achieve their full potential,” the Prime Minister wrote. “Ian said to me once that there was no place he would rather be than in the mountains.”

Leading British and Irish media, including The Irish Times, The Independent, and The Telegraph, widely reported McKeever’s death. A mountaineer described it as “a freak accident,” noting that he had never heard of anyone dying in such a way on this “beautiful mountain”: “I have lost two friends in lightning strikes, including one on the Himalayas — but they are very rare on Kilimanjaro.”

Following McKeever’s passing, his friend Mike O’Shea took over the Kilimanjaro Achievers organization, committing to continue the free climbs for schoolchildren. A year later, the Ian McKeever Children’s Home opened its doors to support children who had lost one or both parents.

All content on Altezza Travel is created with expert insights and thorough research, in line with our Editorial Policy.

Want to know more about Tanzania adventures?

Get in touch with our team! We've explored all the top destinations across Tanzania. Our Kilimanjaro-based adventure consultants are ready to share tips and help you plan your unforgettable journey.