In June 2024, while climbing Kilimanjaro, the Altezza Travel management team made an unexpected discovery — a frog at 4000 meters (13,100 ft). This was a remarkable find, as frogs in Africa typically do not live above 3,000 meters (9,800). We took hundreds of photographs and shared them with the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI). Researchers at TAWIRI suspected that this could be an entirely new species. In collaboration with Altezza Travel, they initiated further research to determine the true identity of these high-altitude amphibians.

We were also referred to Professor Alan Channing, one of the world’s leading experts on amphibians. He speculated that the frog could be an entirely new species and noted that no documented frog species had ever been found at such an altitude in Africa.

Professor Alan Channing is one of the world’s leading experts on African amphibians. He is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa.

Professor Channing is the author of Amphibians of Central and Southern Africa and Field Guide to the Frogs & Other Amphibians of Africa, two of the most important field guides on the subject.

On our website, you can read a recent interview with Professor Channing.

With TAWIRI’s support, plans for the expedition moved forward

It took several months to coordinate schedules, finalize logistics, and identify a suitable weather window that would allow for proper observation of the newly discovered colony. By February 2025, all preparations were complete, and Professor Channing arrived in Tanzania.

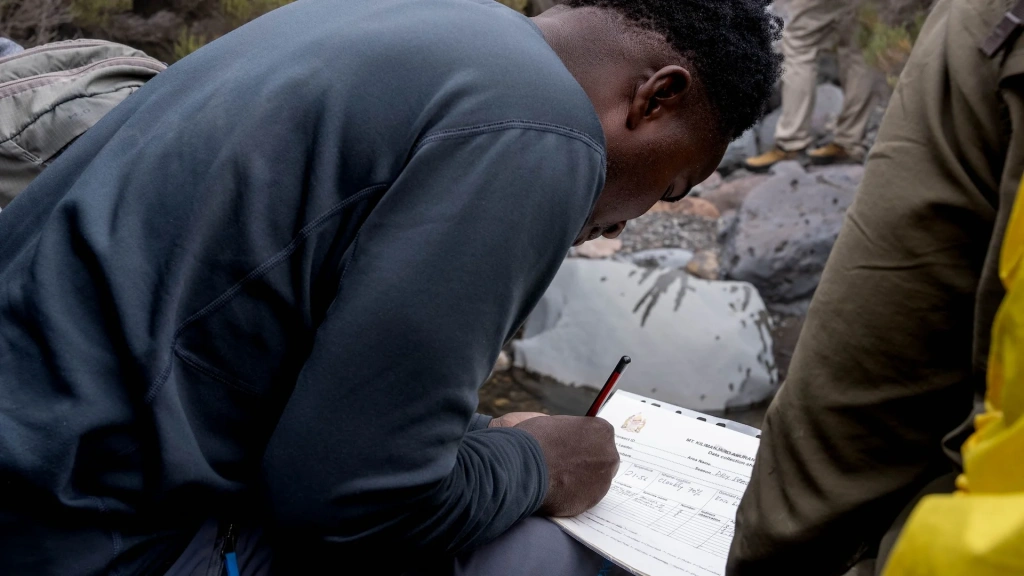

Between February 20 and 25, 2025, guided by Altezza Travel, researchers from the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) explored five known rivers between 3,500 and 4,000 meters (11,500–13,100 ft) on Mt Kilimanjaro and successfully located the frogs.

On March 5, we received the results: the frogs belonged to the Amietia wittei species. This confirmed that they were the same species found in the tropical forests of Kilimanjaro and the Rwenzori Mountains. The discovery overturned the previous belief that Amietia wittei couldn’t survive beyond 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) and revealed their ability to adapt to the harsh conditions of Kilimanjaro’s moorland zone.

More details on the expedition

Altezza Travel organized and fully funded the expedition, paid for the international transport of team participants, and handled all logistics. During the expedition, our company provided tents, food supplies, guides, porters, and oxygen tanks to support work in high-altitude conditions.

The expedition was led by Dmitrii, the head of our climbing department. The chief guide, Peter Lyamuya, along with other guides and porters, ensured that the academic team had everything they needed to focus on their research. Our staff photographer, Jack Wardale, joined the team to document the expedition.

After the expedition, Dmitrii shared his observations from the trip:

«This expedition was very different from standard commercial climbs on Kilimanjaro. We started on the western slope, spending our first night at Simba Camp at 3,700 meters (12,200 ft). It is a desolate place, located between the popular tourist camps Shira 1 and Shira 2. In the vicinity, we found a single tadpole and a young frog, but it was an isolated incident — we didn’t see any others up to 3,900 meters (12,800 ft) in that area. Closer to Shira 2, we observed porters washing dishes in the river. Downstream, there were no frogs, leading us to speculate that dishwashing might be one of the reasons why the frogs' habitat is so limited.

The next day, we moved to our main base camp, Fisher Camp, from where we conducted most of our scientific walks to the rivers. Like Simba Camp, Fisher Camp is not a tourist site. The location was ideal — close to the water sources we planned to inspect and offering a quiet setting where the research team could work without distractions. Most of the tadpoles and frogs we found were in a small pond, about five meters in length and one meter in width, at 3,950 meters. Streams above 4,050 meters (13,290 ft) were dried up.

Together with other guides, I enjoyed this unusual expedition. Unlike standard tourist climbs, where one typically hikes 7–9 kilometers per day and only notices major landscape changes, this time, we stayed in a smaller area and paid attention to the finer details. I didn’t expect searching for frogs to be so engaging, and I had that unique feeling of anticipation, wondering whether we were about to find something exciting. It was a fantastic experience, and I’m eager to take part in future research expeditions.»

The frog colony lives between 3,500 and 4,000 meters (11,500–13,100 ft)

It was determined that the frogs are confined to this specific altitude range, making their habitat extremely limited and, consequently, vulnerable. This colony of Ametia Wittei is particularly fragile, and measures must be taken to ensure its protection.

The threats posed to the colony

While further studies are needed to confirm these findings, the most likely threats to the frogs are as follows:

Water contamination from dishwashing. Porters traditionally wash dishes in Kilimanjaro’s rivers, using cleaning agents that contaminate the water downstream. With nearly 60,000 trekkers visiting the mountain each year, this practice exerts a significant strain on the ecosystem. The impact extends beyond the frogs and other aquatic life — it also affects the communities at the mountain’s base, where these rivers serve as a primary water source.

Water scarcity. Of the four rivers examined, three dry up completely above 3,000 (9850 ft) meters during the dry seasons (June–October and January–March). This was not the case in the past. However, due to ongoing climate change, fewer water sources are available to replenish these streams, which has profound consequences for the entire ecosystem.

According to Wilkirk Mroso from the TAWIRI team, one river that was half a meter (1.5 ft) deep ten years ago is now barely 10–15 cm (3–6 in.) deep. This stark change highlights the severe impact of climate change on Kilimanjaro’s ecosystems.

Predatory birds. Between 3,000 and 3,700 meters (9,850–12,150 ft), Kilimanjaro’s rivers become significantly shallower, creating ideal hunting grounds for water birds such as black-headed herons and green sandpipers. These birds prey on tadpoles and frogs, making them especially vulnerable in exposed waters.

Below 3,000 meters (9,850 feet), water sources are more abundant, providing deeper pools where tadpoles can hide from predators.

What should we do to protect this fragile population

This colony has a significant advantage — they reside within a national park where human activity is limited. This sanctuary shields them from major threats like construction and agriculture, which endanger many species outside protected areas.

However, the practice of porters washing dishes within the park needs to be addressed. This not only threatens the frogs but also impacts other wildlife and the communities that depend on Kilimanjaro’s rivers for drinking water.

We believe that conserving this frog colony, along with other species, should be part of a broader, integrated strategy for Kilimanjaro National Park’s long-term protection.

Acknowledgments

Altezza Travel is proud to have organized this expedition. We are deeply grateful to the following individuals, without whom this mission would not have been possible:

Dr. Ernest Mjingo, TAWIRI Director – for coordinating the TAWIRI research team, providing academic advice, and overseeing the overall management of the project.

Professor Alan Channing – for his scientific guidance throughout the expedition, his inspiration and his invaluable stories about frogs, which deepened our understanding of these and other species.

The TAWIRI field team – Wilirk Ngalason Mroso, Shayo Adolph Felix, Juma Idd Kimera, and Yoel Kitungul – for their dedication to fieldwork, investigating the environment, locating the frogs, and collecting samples alongside the Altezza Travel team.

Dickson Fredrick Muganda, Altezza’s project manager – for coordinating expedition planning, communicating with multiple stakeholders, and ensuring the project’s success.

Peter Alex Lyamuya, Chief Guide – for ensuring the safety and well-being of the expedition team, managing the overall coordination of the trip, and skillfully leading the team through challenging terrain to remote research locations.

Honest Ronald Tillya, Assistant Guide – for his expertise in crew management, navigation, and providing critical support to the expedition members.

Jackson Ramweli Macha, Assistant Guide – for his dedication to assisting the team, ensuring smooth navigation, and offering crucial support throughout the expedition. His experience and reliability were instrumental in reaching key research sites.

Novati January Kombe, Porter – for his tireless support throughout the expedition. He remained with the researchers at all times, assisting in locating and collecting samples while also carrying essential research tools and supplies and helping the team navigate challenging terrain.

All content on Altezza Travel is created with expert insights and thorough research, in line with our Editorial Policy.

Want to know more about Tanzania adventures?

Get in touch with our team! We've explored all the top destinations across Tanzania. Our Kilimanjaro-based adventure consultants are ready to share tips and help you plan your unforgettable journey.